Why Second Chances Matter

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

Phyllis Richey is an Alabama parole success story.

Phyllis Richey has worked as a job trainer with people coming out of prison since she was released on parole in 2018. She is a great example of why second chances matter and why Alabama’s parole board sorely needs reform.

In 1998, Phyllis Richey was struggling through a divorce, and began drinking heavily. One night she caused a drunk driving accident that killed two people. Phyllis was gravely injured, lost a leg and was sent to prison. She became parole eligible after 10 years, but it would take another decade in prison for a second chance.

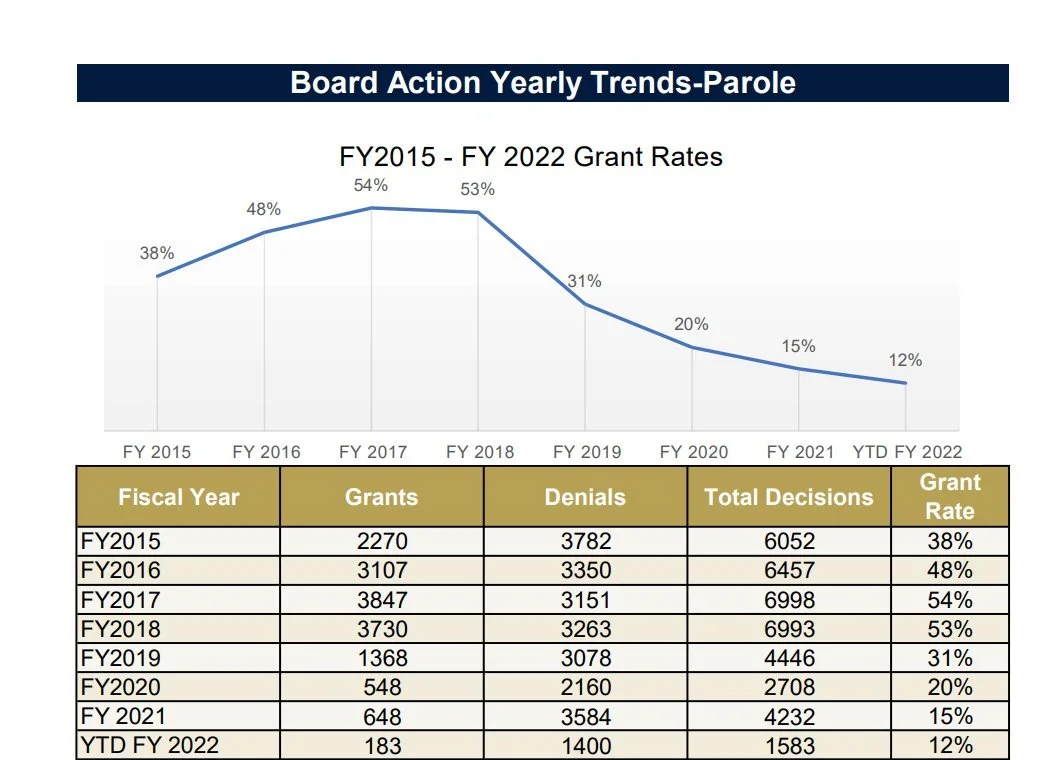

It has never been easy to make parole in Alabama, but since 2019, the percentage of parole-eligible people who are denied release by Alabama’s parole board has more than doubled. When Phyllis finally made parole after 20 years, she'd earned over 130 certificates in prison, but it was her fourth time to be considered. The first three times she was denied due to opposition from the victims in her case. After all those denials, she was depressed & almost gave up.

"The first time I was devastated because I’d done everything that was asked of me,” Phyllis said. “When I didn’t make it the second time, I thought I would never make it out of there." Despite her hopeless situation, Phyllis continued to work on her own rehabilitation and growth in prison, maintaining a clear prison record, working various jobs, tutoring other women and helping facilitate the prison’s rehabilitation program.

Source:

Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles

Phyllis believes she's one of the last people with a violent conviction released on parole before 2019 changes on Alabama's parole board led to record denials. The current board, led by former prosecutor Leigh Gwathney, appears to be following a categorical ban on paroling anyone with a conviction involving injury or loss of life.

Phyllis knows she got out right before the door slammed. "I think about everyone I left behind," she said. "There are good people in prison who made bad choices, but they deserve a fair chance at parole. This board acts like it's their job to re-sentence people and that's not right."

The mixed messages in policy spread despair like a sickness. Incarcerated people are told to work hard, follow the rules & take programs to improve their parole chances, but when they're finally considered, their prison records or length of time served don't seem to matter to the parole board.

“They are denying people with perfect prison records," Phyllis said. "People who've served 15, 20, 25, even 30 years or more. It breaks my heart." This means a person can have 50 disciplinary citations or zero on their prison record, but the board treats them the same. If they have a violent conviction, they're denied.

The message this sends: what you do with your time doesn't matter. Your rehabilitation isn't important. Following the rules won't make a difference. Phyllis says the board's unwillingness to grant parole turns almost every parole-eligible sentence into life without parole. “It feels like no matter how much time we’ve done, it’s never enough," she said. "By the grace of God I got out after serving 20 years, but I know it was by a hair. I have not forgotten the women I left behind. We have made mistakes, but we are not who they say we are."

When Phyllis was released, she was shellshocked and sat on her bed in a halfway house for three days, not knowing what else to do. Prison did not prepare her for freedom, so she relied on support from formerly incarcerated mentors at the Offender Alumni Association, who helped guide her transition. Phyllis works as a construction job training instructor, teaching in parole "day reporting centers" across the state, but class sizes have dwindled. "Because they're not letting anyone out, we might have 1-2 students where we used to have 8-12," she said. "It's sad."

Phyllis training a student

The program is called A Cut above the Rest and was started by two women who Phyllis served time with at Tutwiler Prison. "Everybody that touched my heart and helped me in any kind of way when I got out was an ex-offender," Phyllis said. "I want people to know that."

(Phyllis pictured with three members of Offender Alumni Association.)

Alabama's 3-member board, appointed by Governor Kay Ivey, will not say why they are categorically blocking parole for thousands of eligible people, even though their sentences include the possibility of parole. The board votes against its own guidelines in 2/3 of cases, but doesn't have to explain why. A bill to require the board to provide reasons for straying from its own parole guidelines will likely not pass this legislative session. It would have been a good start to increase transparency and accountability on this board, and had bipartisan support, but not enough.

For Phyllis, it's good reason to keep sharing her story. She believes people who commit crimes should be held accountable, but redemption and second chances should be the goal of prison, not continuous punishment. "People can change,” she said. “I'm grateful I got the chance to prove myself."

Phyllis Richey hopes Alabama’s current parole board will begin to recognize the importance of second chances.