Never-Ending Punishment

How Alabama’s Record Pardon Denials Punish Law-Abiding Citizens

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

Timothy King with his family. Alabama’s Board of Pardon and Paroles denied his pardon in August, 2021.

On August 12, 2021, Timothy Chavis King was feeling good about his chances. He got up early, put on a suit and drove from Mobile to Montgomery to appear in person at his first pardon hearing in front of Alabama’s Board of Pardons and Paroles.

King, 39, has two drug possession convictions on his record dating back to 2004. The married father of two young boys was seeking a pardon to restore his record and shake the mistakes of his past. He’d like to vote and improve his job prospects, especially as his business has been slow during the pandemic.

“I’m tired of being bound,” King said. “I’m a family man now. I own a business. I wasn’t a drug dealer or anything. I was just young and stupid.”

King’s convictions, which involved crack cocaine and marijuana, were not serious enough to send him to prison. Instead, he did two separate stints on supervised probation after once spending 70 days in jail after an arrest.

“I told myself, that’s the last time I would ever put myself in that situation,” he said.

After his second probation term ended, King earned his GED and worked his way through community college, graduating with a degree in barbering. In 2018, he opened his own barbershop and has since bought his first home. He shared these details when he appeared before the 3-member board at his August hearing.

“I talked to them and really poured my heart out and let them know who I was,” he said. But board members surprised King by asking about a prior domestic violence arrest for which he was not convicted. He said the incident involved a past relationship and charges were dropped.

“I feel like I shouldn’t have to talk about that,” he said. “That was a not guilty case. She kept saying ‘tell me what happened,’ but there’s nothing to tell. I wasn’t found guilty of that.”

King said questions from the board kept coming. They asked if he had a drug problem, when he last smoked marijuana and whether he could pass a drug test.

“I told them I smoked marijuana when I was in California where it’s legal,” he said. “If I would have known it was going to go like that, I would have lied.”

After King was finished speaking, a victim’s services officer (VSO) from Mobile’s District Attorney office stood up and voiced opposition to his pardon request, citing his drug convictions as a reason to deny a pardon.

“She is talking like she knew me, like we were enemies, and I am a ruthless criminal,” King said. “They treated my whole situation like I was a prisoner and I’ve never even been to prison.”

A message left for the VSO was not returned. A search of court files did not turn up any record of King’s domestic violence arrest.

When the board announced they voted to deny King’s pardon, he left the hearing, got into his car and cried. He can apply again in two years but said he’s not sure what else he could do to improve his chances.

“They shot me down and I didn’t understand,” he said. “I wasn’t ready for that. I feel like if I can’t have all my rights, what’s the purpose of being a citizen? I mean, am I a citizen?”

The purpose of a pardon is to restore a person’s civil and political rights after a criminal conviction. Only people who have completed their sentences or three successful years on parole are eligible to apply, so there’s no public safety benefit to a denied pardon.

Earlier this year, ACLU of Alabama’s Campaign for Smart Justice reported on the precipitous drop in pardon grants under the current board, led by former prosecutor Leigh Gwathney. According to the latest data available on the ABPP website, the board has denied 76 percent of pardon applicants in FY 2021.

This represents a 70 percent drop in pardon grants compared to FY 2018, when the prior board granted pardons at a rate of 80 percent. Year-to-date data from July 2021, the latest currently available, has the current board’s pardon grant rate hovering at a historic low of 24 percent.

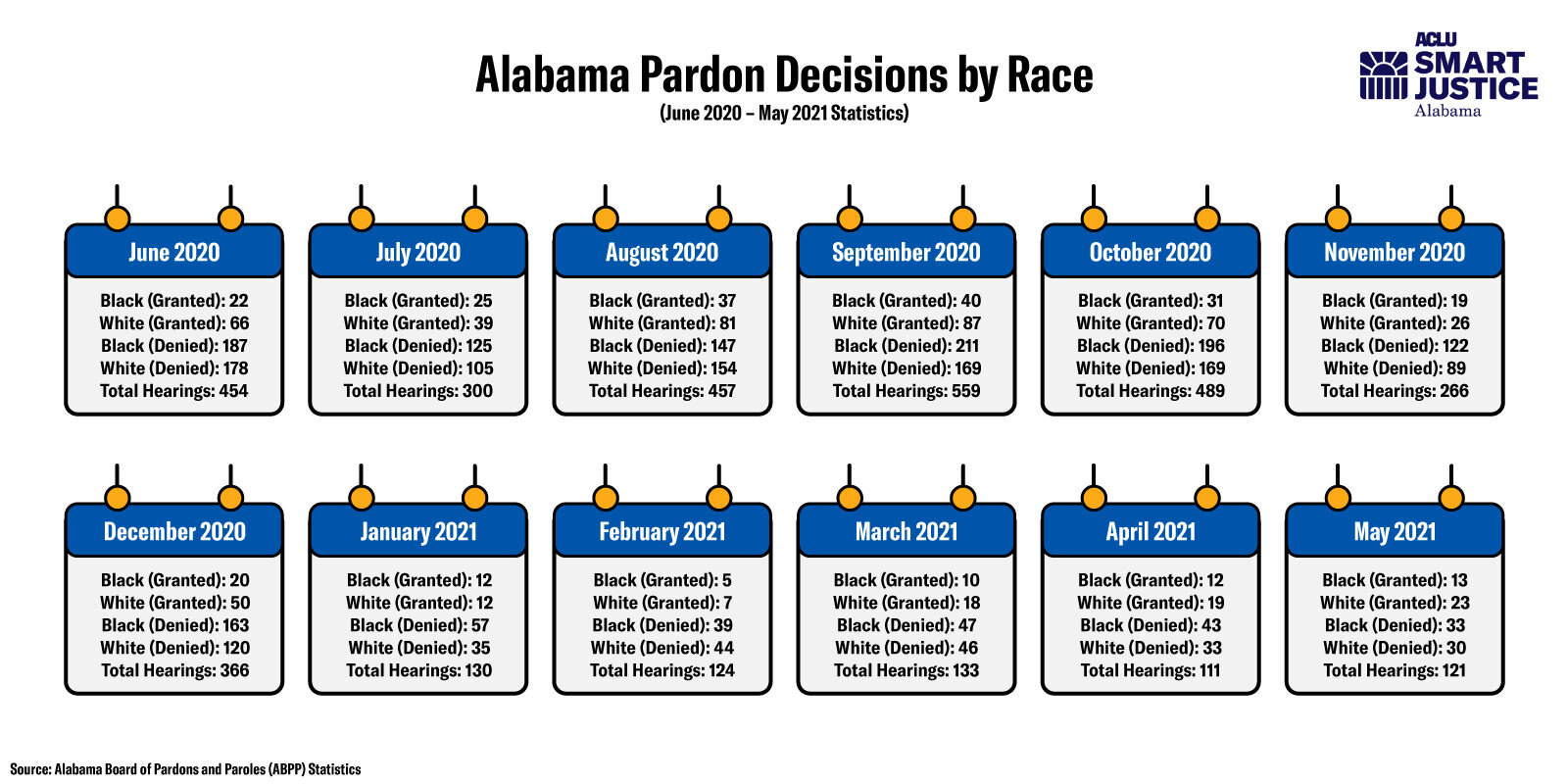

Recently obtained ABPP data on pardon results by race shows a stark racial disparity in pardon hearing results. As indicated in a yearlong snapshot of data, white applicants were granted pardons at double the rate of Black applicants. Between June 2020 to June 2021, 504 white applicants were granted pardons at a rate of 14 percent while in the same time period, only 254 Black applicants were granted pardons at a rate of just 7 percent.

Timothy King, who is Black, was one of 9 people on the pardon docket that day, with the board granting 5 pardons and denying 4. ABPP does not publicly release race or prior convictions of pardon applicants, but a search of court records shows of those denied, 2 people are Black and 2 are white.

Of those granted pardons, records located for 4 of the 5 people show 2 are Black and 2 are white. Past convictions for those whose pardons were granted included drug trafficking and manufacturing of a controlled substance, which are more serious charges than King’s two simple drug possessions.

But trying to figure out why one person is granted a pardon while another is denied is an exercise in futility. State law gives the board full discretionary authority to grant or deny pardons, and no public list of guidelines on how they make decisions is available. The board does not offer any reasons about why it denies a pardon and applicants cannot ask for a review or appeal a decision.

The inconsistency in outcomes is particularly frustrating for Montgomery-based attorney Andrew Skier. He’s represented several clients who were recently denied pardons, which he believes would have been easily granted under previous boards.

One case involved a single mother who asked to be identified as Rachel, which is not her real name. In June, she was denied a pardon for a single drug conviction which has prevented her from advancing in her career.

Rachel, who is white, hired Skier to help her seek a pardon with the hope that she could finally get certified as a loan officer in the mortgage industry. While working in the field, she learned the ropes, then took a 20-hour online certification class and aced the exam.

“But I still can’t get licensed because I’m a felon,” Rachel said. “I was hoping with a pardon I could get licensed as a loan officer and increase my income.”

Rachel has also had problems finding housing, but recently purchased her own home, a personal achievement after facing years of barriers with rental companies.

“Everywhere does background checks and as soon as they see I have a felony, they don’t want me in their apartment complex,” she said.

Rachel was an unlikely person to end up in trouble. In the last decade, she was a serious student at UAB, the first in her family to go to college. She wanted to work in research and planned to get a master’s degree and a Ph.D. after graduating. Instead, she ended up in jail.

While working in a lab, she became friendly with a study participant who told Rachel she had breast cancer and was going through chemotherapy. The woman messaged Rachel on Facebook asking if Rachel could help her buy marijuana that she claimed she needed for pain. Rachel told her she didn’t do drugs and didn’t know where to find them, but the woman persisted, playing on Rachel’s emotions.

“I don’t know how many times she asked me, but it was over and over for months,” Rachel said.

Eventually, Rachel gave in and asked around, identifying a source for the weed, finally telling the woman she would help her out. The woman asked Rachel to meet her son and the two texted about meeting in a Wal-mart parking lot. Rachel met the man and sold him a small amount of marijuana for $20.

“I felt like I was helping out someone in need,” she said. “I felt like it was medicine. Looking back, it was stupid. I should have said no.”

Rachel met the woman’s son two more times for a similar transaction. A few days after the third meeting, police came to her apartment and told her they had recordings of her dealing drugs. The son of the woman had turned Rachel in, likely to help his own criminal case. Rachel was trapped.

“What you’ve got is a person who had no intention of breaking any laws until she was contacted by this person, and that person created the intent to break the law,” Skier explained. “That’s classic entrapment.”

A warrant was issued for Rachel’s arrest, and she was pulled over by police and taken to jail. Her car was repossessed, she lost her apartment and all her belongings inside. Suddenly her young, promising life imploded.

“It was a snowball effect, and all the sudden I’ve lost everything,” Rachel said. “I felt like my whole life plan changed.”

She spent almost a month in jail before her first court hearing. To make matters even more difficult, Rachel was recovering from surgery for a broken leg when she was arrested and spent the whole time in jail experiencing significant pain. The jail took away her pain medication even though she had a prescription from her surgeon.

Rachel met her public defender for the first time in court almost a month after her arrest. She remembers him asking if she wanted to get out of jail that day. She told him yes, and he advised her to plead guilty, so she did. Rachel faced three years of probation and $1,280 in court fees. She moved in with her mother and with the conviction of distribution of a controlled substance on her record, the only job she could land was making minimum-wage.

“I had just gotten out of UAB with my bachelor’s degree, and here I was living with my mom, working for $7 an hour at a BBQ restaurant,” Rachel said.

In the six years since this happened, Rachel completed probation, paid off her fines and did everything the system asked of her. She’s now mother to a toddler and hoped earning a pardon could help her start a new chapter no longer burdened by the worst mistake of her life.

Her pardon hearing was set for June when the board had still not resumed in-person hearings. In May of 2020, the board decided to hold pardon and parole hearings behind closed doors, with no witnesses allowed to testify, after suspending hearings for two months due to COVID.

Skier submitted Rachel’s pardon application, letters of recommendation and even a video of Rachel addressing the board. On the day they decided her case, Rachel spent the afternoon refreshing the results page on her computer, anxious to learn her fate.

“I was really hoping for a fresh start,” she said. “I was ready for someone to say, we know you screwed up, but we’re going to give you another chance.”

Instead, she learned the board denied her pardon, but has no idea why. With parole decisions, state law requires the board to send reasons why they voted to deny in a letter to candidates in prison. But with pardons, no such requirement exists. This lack of clarity on why the board votes no forces denied applicants to simply guess on how to improve their chances for a pardon in the future.

“This just feels like a weight on my shoulders that’s going to be there forever,” said Rachel.

The board has not responded to requests on reasons behind the recent downward trend and Bureau Director Cam Ward would only say previously that the bureau has no say in how the board votes.

Ward is chairman of the recently formed state commission on re-entry, with the stated goal of improving services to formerly incarcerated citizens. It’s hard to imagine a more crucial service than the restoration of civil rights through a pardon. If the commission truly wants to aid in re-entry and address continued disenfranchisement that people face after prison, members should demand that board members explain why they’re denying pardons to the vast majority of qualified applicants.

Beth Shelburne is an investigative reporter for the Campaign for Smart Justice with the ACLU of Alabama. For investigative reporting on Alabama’s prison and pardons & paroles systems, follow her on Twitter at @bshelburne.

![[9-2021-Updated]-Alabama-Pardon-Grants-Fall-to-Historic-Lows-[TWITTER][4].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ff49b04c6eb3c3de1ae3d62/1632750245830-TKBH21SX10KCQ8I4CPBF/%5B9-2021-Updated%5D-Alabama-Pardon-Grants-Fall-to-Historic-Lows-%5BTWITTER%5D%5B4%5D.jpg)