Report: Alabama’s Habitual Offender Law

DRIVING MASS INCARCERATION SINCE 1977

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

In 2020, more than 500 people are serving life without parole under Alabama’s draconian “Habitual Felony Offender Act” or HFOA. The law, passed at the dawn of the tough-on-crime era, mandates longer sentences each time someone commits a felony, regardless of the time between offenses. The law was amended in 2000, ostensibly to make it less severe, but it still mandates a life without parole (LWOP) sentence for anyone convicted of a Class A offense if they have three prior felonies on their record and one of them is a Class A offense, even if the prior offenses were committed decades ago. Class A offenses include murder and rape, but also robbery, burglary, drug trafficking and manufacturing of a controlled substance.

In 1976, Federal Judge Frank Johnson found Alabama prisons to be overcrowded, violent and “wholly unfit for human habitation.” That didn’t stop Alabama’s Legislature from passing the HFOA in 1977, one year after Johnson’s landmark ruling. The new law was considered the harshest in the nation because of its ironclad mandatory punishments: a life without parole sentence for anyone convicted of a Class A offense with any three prior felonies on their record and a life sentence for anyone who was convicted of a Class B felony with any three prior felonies on their record.

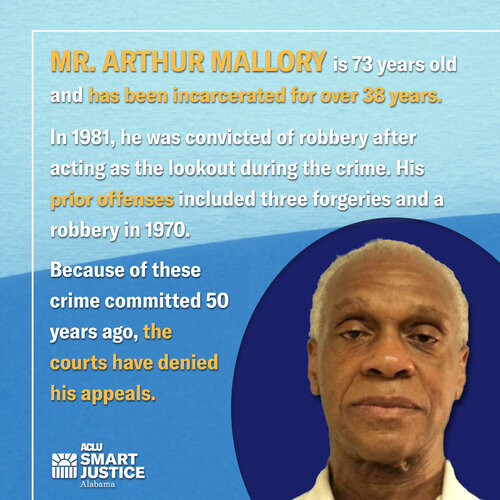

This meant someone could be sentenced to die in prison for a single burglary or robbery and three prior forgery or drug convictions. The outsized punishment resulted in hundreds of people being sent to prison for the rest of their natural lives for a handful of offenses committed when they were young, many involving no bodily injury. Alabama’s law is vastly out of line with similar “three-strike” laws in other states because it doesn’t account for the time between prior offenses and allows for multiple offenses to arise from a single incident.

From 1968 to 2010, Alabama’s prison population had a stark trajectory of growth. The population began to decrease in 2011, likely due to increased paroles and the 2015 sentencing reforms. However, the population is rising again due to an unprecedented drop in paroles under the current administration.

In 2014, Alabama’s legislature repealed the retroactive application of the 2000 amendment to the HFOA, taking away the only avenue available for this population to apply for a sentence reduction. The legislature did this at the request of Alabama’s Court of Criminal Appeals, which complained that the law was being used by “prolific pro se litigants to file frivolous petitions.” The result of the repeal means hundreds of people who wouldn’t be sentenced to LWOP today are trapped in Alabama’s violent and overcrowded prisons until they die with no legal means for release.

WHO IS IN THE LWOP POPULATION UNDER HFOA?

The racial disparity resulting from Alabama’s HFOA is significant. Three out of four people sentenced to die in prison under HFOA are Black. According to the latest data available from the Alabama Sentencing Commission, in October 2019, 527 people were serving life without parole for offenses other than murder, with the most common triggering offenses being robbery, rape and burglary. However, an analysis of the population revealed at least 300 people serving LWOP under HFOA have no sex offenses on their records, and 165 people have no prior Class A felonies, which means they wouldn’t be sentenced to life without parole today.

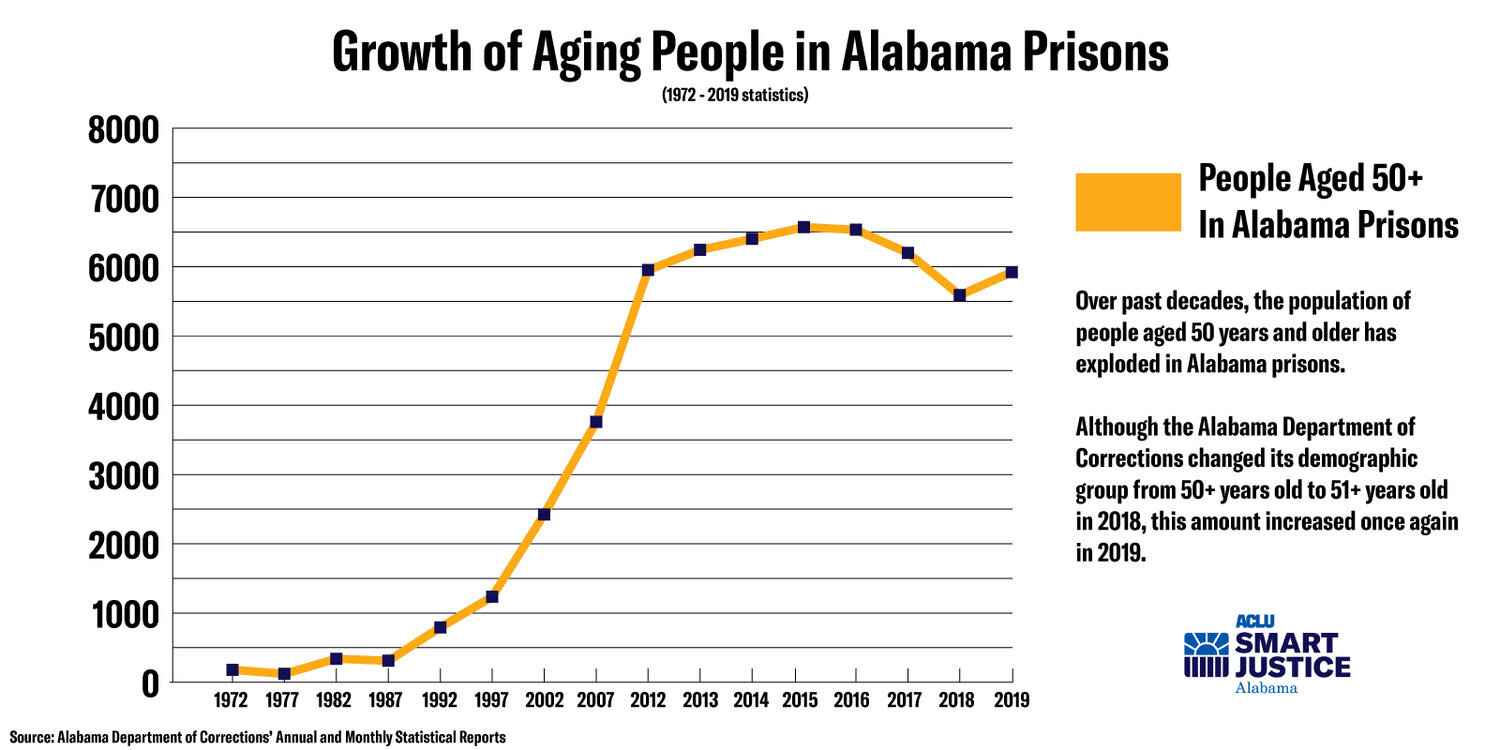

Over past decades, the population of people aged 50 years and older has exploded in Alabama prisons. Although the Alabama Department of Corrections changed its demographic group from 50+ years old to 51+ years old in 2018, this amount increased once again in 2019.

112 men in this population committed their last offense in the 1980’s. 100 of them have served at least 30 years in prison. 208 people, or 69 percent of the 300 people in this population with no sex offenses, are over 50-years old. The average age in this population is 54, with 87 people between 60-69 years old and 19 people over 70.

HOW HAS HFOA CONTRIBUTED TO ALABAMA’S UNCONSTITUTIONAL PRISONS?

HFOA’s effect on Alabama’s prison system was immediate and dramatic. When the law was passed, Alabama prisons incarcerated fewer than 4000 people. By the year 2000, the system, designed to hold 13,000, was bursting with 25,000 people. Today there are over 6,100 people serving longer, enhanced sentences under Alabama’s HFOA, with over 1,100 serving life and 527 serving LWOP, which is the harshest possible punishment next to a death sentence.

Despite new sentencing guidelines, which became presumptive in 2013, the HFOA is still an available tool for prosecutors, who invoke it at their discretion. This allows for enormous disparity in sentencing. Since 2003, 177 people have been sentenced to LWOP under the HFOA. Because of the continuous flow of people admitted into Alabama prisons with permanent sentences, the population serving LWOP under HFOA never meaningfully changed, despite reforms intended to reduce terminal sentences.

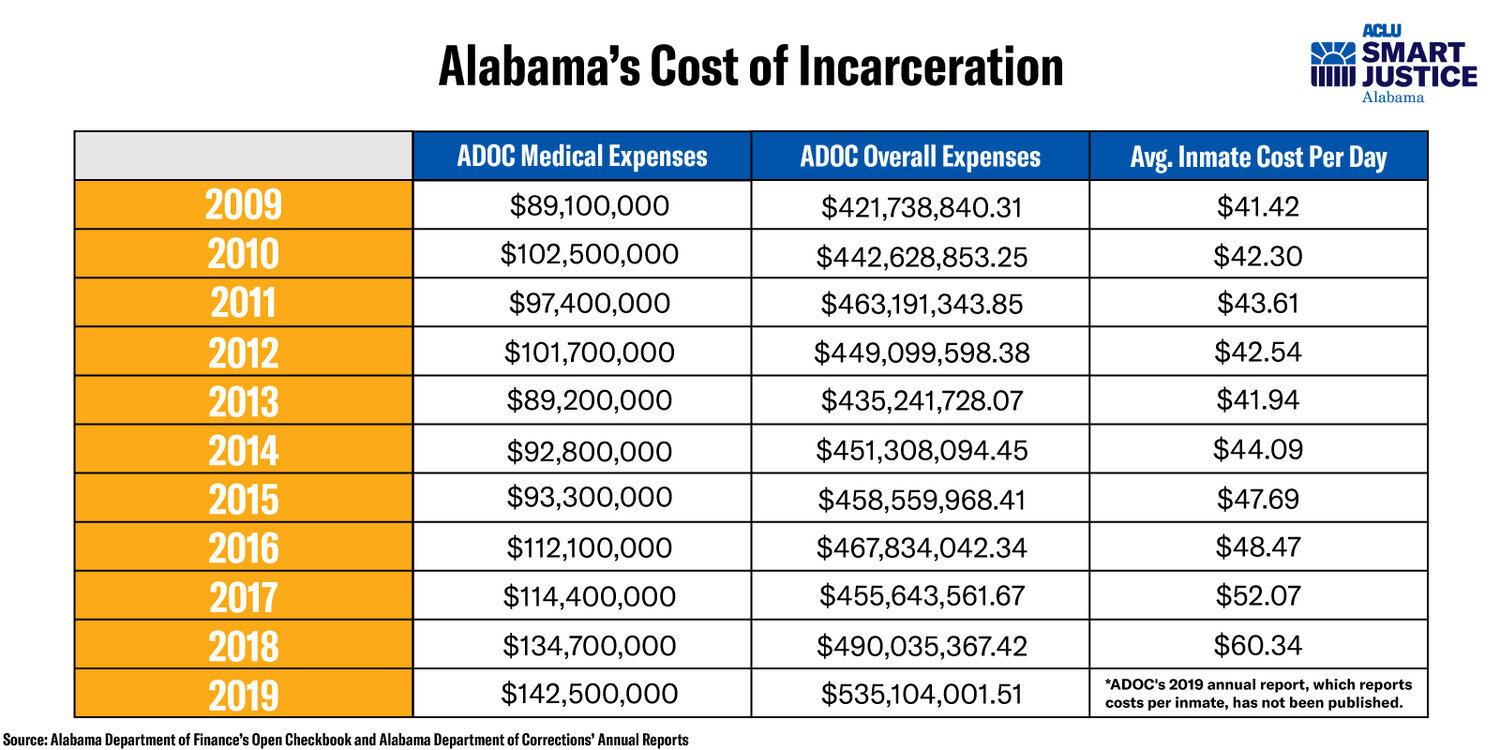

Alabama prisons are horrifically overcrowded and violent, largely due to long-term and life sentences that resulted from the HFOA. The cost of incarcerating people rises dramatically as they get older, but evidence strongly supports a decreased risk of reoffending as people age. Alabama simply cannot afford to warehouse people who pose no threat to public safety in overcrowded, violent prisons.

Beth Shelburne is an investigative reporter for the Campaign for Smart Justice with the ACLU of Alabama. For investigative reporting on Alabama’s prison and pardons & paroles systems, follow her on Twitter at @bshelburne.

![[3.0]-Racial-Disparities-From-Alabamas-HFOA.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ff49b04c6eb3c3de1ae3d62/1628434649891-CZ6SEVGD6MZHCTMQ9QVO/%5B3.0%5D-Racial-Disparities-From-Alabamas-HFOA.jpg)