Report: Grim Outlook For Parole-Eligible People In Alabama Prisons

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

Internal documents from Alabama’s Bureau of Pardons and Paroles recently obtained by the ACLU of Alabama paint a picture of internal strife and a parole board that blatantly ignores its own guidelines despite an unprecedented backlog of parole-eligible people coupled with the lowest number of parole hearings and grants on record. The documents also reveal a concerning racial disparity with white candidates granted parole at double the rate of Black candidates.

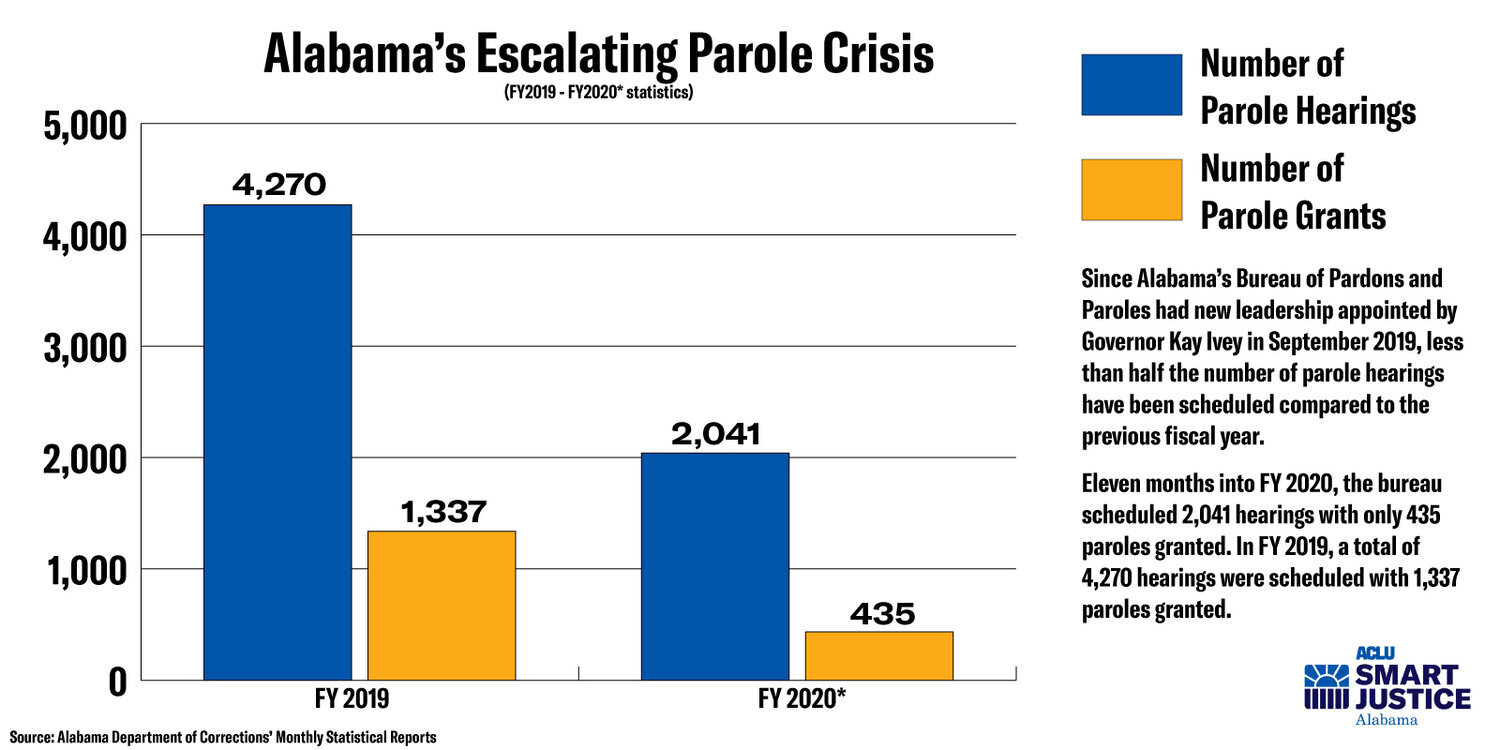

Even before COVID-19, the current parole bureau and board have overseen the lowest number of parole hearings and the fewest parole grants in state history. Since new leadership appointed by Governor Kay Ivey arrived in September 2019, less than half the number of hearings have been scheduled compared to the previous year. Eleven months into FY 2020, the bureau scheduled 2,041 hearings with only 435 paroles granted. In FY 2019, a total of 4,270 hearings were scheduled with 1,337 paroles granted.

Since Alabama’s Bureau of Pardons and Paroles had new leadership appointed by Governor Kay Ivey in September 2019, less than half the number of parole hearings have been scheduled compared to the previous fiscal year. Eleven months into FY 2020, the bureau scheduled 2041 hearings with only 435 paroles granted. In FY 2019, a total of 4270 hearings were scheduled with 1337 paroles granted.

The documents obtained by ACLU include data that tracks how closely the parole board is adhering to its own guidelines, which shows a massive disparity between the recommended parole grants and the actual rate at which the board is granting parole. Alabama’s parole board is required by state law to establish an internal policy known as “parole guidelines” to help determine who should and should not be paroled. The guidelines include an evidence-based risk assessment to evaluate parole candidates, as well as other factors like the severity of offense, institutional behavior and input from victims and law enforcement. The board considers all of this information “while applying professional judgement in each case,” according to the current guidelines.

Parole Guideline Conformance Rate by Month, Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, August 2020

A chart tracking the data shows a year-to-date recommended parole grant rate of 71 percent, while the board’s actual grant rate stands at 17 percent. The chart indicates the parole board has a “conformance rate” of 48 percent, meaning the board is making decisions that conform with its own guidelines in less than half of all cases.

The same chart reveals a stark racial disparity, presented in a breakdown of parole grants by race from May through July.

The data shows the board only granted parole to 51 Black candidates out of 442 considered, at a grant rate of just 12 percent. By comparison, the board granted parole to 116 white candidates out of 469 considered, at a grant rate of 25 percent. The data further shows the board conformed to its own guidelines in 51 percent of cases involving white candidates, but only 44 percent of cases involving Black candidates.

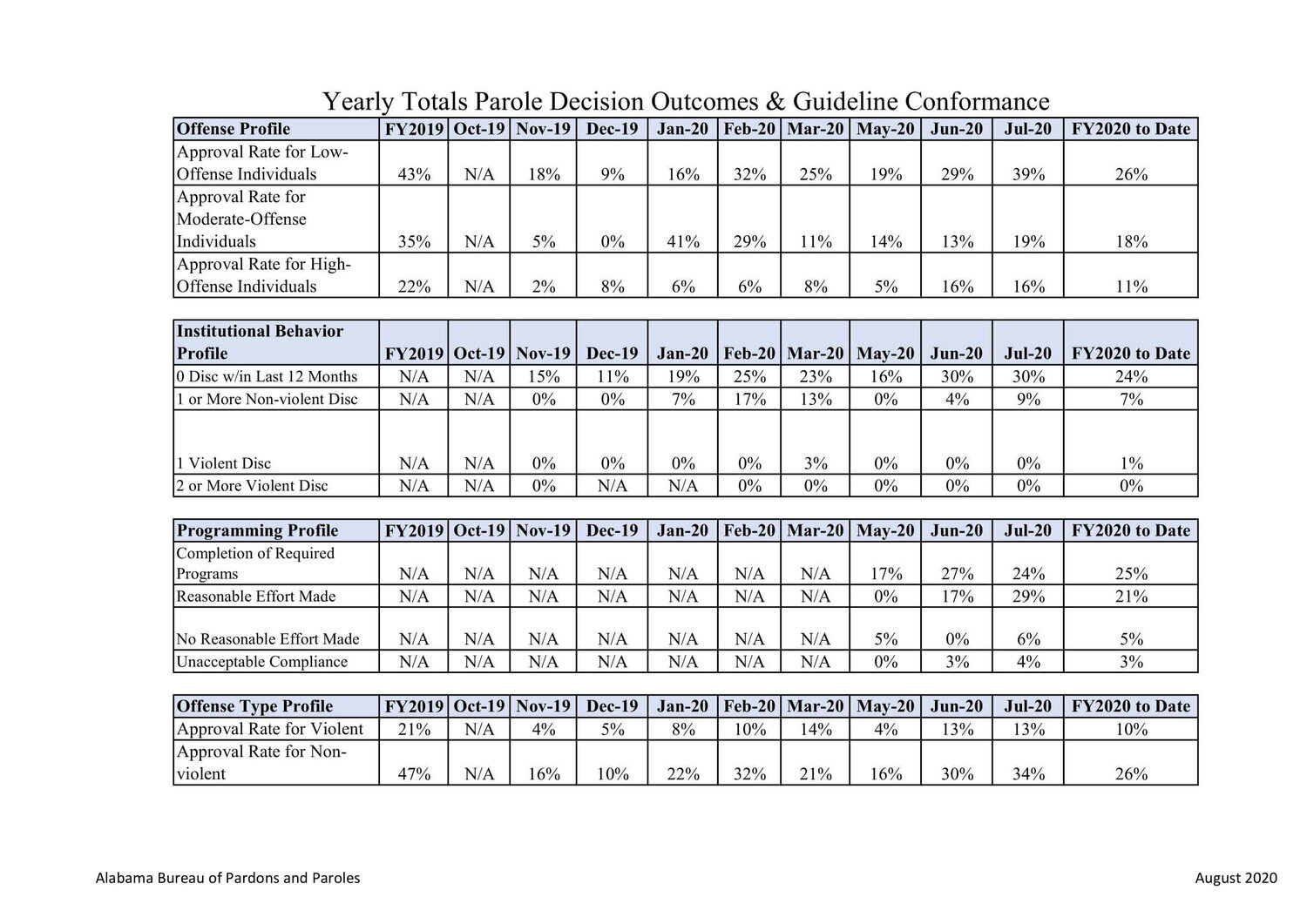

Yearly Totals Parole Decision Outcomes and Guideline Conformance

The current parole board is also much more likely to grant parole to women over men. The data of parole results shows the board granted parole to 71 women out of 170 considered, at a grant rate of 42 percent. By comparison, the board granted parole to 231 men out of 1610 considered, at a grant rate of just 14 percent. The board conformed to its own guidelines in 60 percent of cases involving women, but only 46 percent in cases involving men.

The documents obtained by ACLU of Alabama also include internal tracking of the board’s reasons for granting or denying parole. The most common reasons for denying parole, both before and after the guidelines were amended, include “severity of present offense is high” and “negative input from stakeholders,” which includes victims and law enforcement. Since July, the board has used the severity of offense reason to deny parole in 71 percent of cases and negative input in 62 percent of cases. For a person being considered for parole, the severity of their offense cannot change during their incarceration. This board is clearly weighing static factors more heavily than variable factors, like a candidate’s institutional conduct or record of rehabilitative programs.

Reasons for Granting and Denying Cases Since New Parole Guideline Tracking

Because of the weight board members place on static factors and stakeholder input, people convicted of offenses defined as violent are much less likely to be granted parole, even if the offense was committed decades prior to a present offense defined as nonviolent. Since new leadership assumed control in September, 2019, only 114 candidates with violent offenses have been granted parole. Of those, the majority were convicted of crimes that did not involve physical harm or actual violence to a victim, like third degree burglary or drug trafficking. These two offenses accounted for more than half of the people defined as “violent offenders” who have been granted parole.

Based on a document tracking the parole decision outcomes and guideline conformance, the current board is denying more people parole based on the type of offense.

There has been a 50 percent drop in the approval rate for individuals with a “high offense profile,” from 22 percent in FY 2019 to just 11 percent in FY 2020 to date. The approval rate for “violent offenses” was 21 percent in FY 2019, but stood at 10 percent for FY 2020 at the end of July.

Yearly Totals Parole Decision Outcomes and Guideline Conformance

Because of Alabama’s overly broad definition of violent crimes, the majority of people incarcerated in Alabama prisons have been convicted of a violent offense. To deny all of them a meaningful chance at parole based exclusively on their offense will only increase the overcrowding and warehousing in Alabama prisons, in which over a quarter of people are over the age of 45.

ACLU of Alabama also obtained email communication between Charlie Graddick, Director of the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles and Leigh Gwathney, chair of the Parole Board regarding the current parole and pardon backlogs. The correspondence begins with a June 22 letter from Graddick informing Gwathney that the Bureau will increase hearings to four days a week, instead of three, at a rate of 40 to 60 hearings per day. “As you likely know by now, the Board’s overall hearings numbers for this fiscal year are on pace to be the lowest on record,” he writes. He also informs her that pardon hearings must be restarted at a rate of 10 hearings per day “to address the agencies tremendous pardon backlog.”

Gwathney responds with a June 23 letter reminding Graddick that the Bureau determines the number of hearings, not the Board, and “it appears that the Bureau staff is uncertain at this time how many cases its staff can prepare for the board to hear.” Graddick answers with a June 24 letter, informing Gwathney that based on her feedback, “Board operations will plan to immediately schedule hearings at a rate of 60 per day beginning the first week of August,” to include no less than 10 pardon hearings per day.

Despite the directives arising from a contentious back and forth, the Bureau still failed to reach its targets. An examination of parole and pardon hearing minutes reveals the board averaged a total of 50 hearings a day in August including pardons and paroles, not the 60 hearings that Graddick demanded. According to the hearing minutes, in August the board heard an average of 39 parole cases three days a week compared to July, when the board heard an average of 25 paroles cases three days a week.

In the last two years, Alabama’s parole system has undergone tremendous upheaval and change, resulting in a precipitous drop in parole grants beginning in 2018 and a dramatic reduction in the number of hearings held under the current administration, exacerbating the massive backlog of parole-eligible people in prison who are waiting for a hearing, sometimes for years. Eleven months into FY 2020, the number of hearings scheduled is less than half the hearings held in FY 2019 and parole grants in FY 2020 amount to less than a third of parole grants from FY2019.

From FY 2013 to 2018, Alabama’s parole grant rate steadily grew. This increase in paroles, as well as Alabama’s 2015 sentencing reforms, caused the state’s prison population to decrease. However, after a change in administration two years ago, the parole grant rate began to starkly drop. FY 2020 is estimated to reflect a 17% parole grant rate, which will be the lowest rate in seven years since FY 2013.

The crisis in Alabama’s parole system is all the more appalling when considered against the backdrop of the U.S. Department of Justice findings in 2019, that severe prison overcrowding amounts to cruel and unusual punishment, along with the global COVID-19 pandemic, in which incarcerated people face a much higher risk of infection and death. Governor Ivey and ADOC’s solution is to hook taxpayers into a 30-year, $2.6 billion lease of mega-prisons built and owned by private prison companies. However, looking closely at Alabama’s failing parole system should serve as a good reminder for why the solution to Alabama’s prison crisis demands the hard work of reform, not spending more taxpayer dollars on new buildings to incarcerate even more citizens.

LINKS TO DOCUMENTS:

Beth Shelburne is an investigative reporter for the Campaign for Smart Justice with the ACLU of Alabama. For investigative reporting on Alabama’s prison and pardons & paroles systems, follow her on Twitter at @bshelburne.