Alabama Prison Deaths Leave Grieving Families With No Answers

The day before Richard Jason Reed died inside Bullock Correctional Facility on May 2, he called his family and told them he was scared. He said other men incarcerated inside the prison had threatened him with a knife and he did not feel safe.

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

His sister, Misty Reed Tipton, said her brother asked his father to call the prison warden and request that he be moved into a safer dorm. It was late on a Friday afternoon, so his father promised to make the call the following Monday morning, but his son wouldn’t survive the weekend. A prison chaplain called the family Saturday night around 11:15 p.m. to tell them that Jason was dead.

“I asked what happened and he said he couldn’t release any of that information,” Misty said, still in shock over her brother’s sudden death. “To this day we have no clue what happened to him. That’s what is so hard. We had to bury him and we have no idea why.”

Richard Jason Reed. Photo provided by Misty Reed Tipton

The family of Jason Reed is one of dozens across the state grappling with the unexpected and unexplained death of their loved one inside an Alabama prison. In 2019, a record 29 deaths due to homicide, suicide and drug overdose occurred in the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC), making it the deadliest prison system in the nation. Even before the agency struggled to prevent the spread of coronavirus in its horrifically overcrowded facilities, men and women incarcerated in ADOC facilities experienced one of the highest death rates on earth.

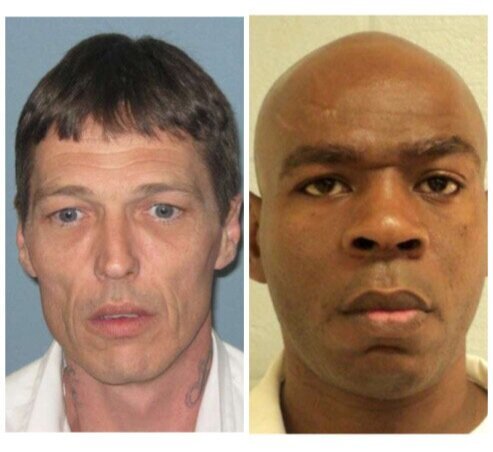

Reed was one of multiple people who have died in ADOC custody during the COVID-19 pandemic, but whose deaths were unrelated to the virus, according to the agency. Two men died at St. Clair Correctional Facility the following week of likely drug overdoses. ADOC confirmed Stephen Smith died May 6 and Frondesse Jones died May 9.

Stephen Smith (L) and Frondesse Jones (R) Photos: ADOC

A spokesperson for ADOC said the official cause of death in each case was pending autopsy results, but foul play was not suspected. Sources inside St. Clair said both men had taken controlled substances and likely overdosed.

A man incarcerated at St. Clair wrote a letter about the deaths, expressing outrage over the loss of life and frustration over the lack of action.

“Neither of these men should have died,” he wrote. “Since March 17, we’ve been on semi-lockdown; no visitors, no support staff has been allowed to enter this facility. Yet there has not been a shortage of any drug. When a prisoner ‘wigs out’ on synthetic drugs, they are sent to the infirmary until they are through ‘wigging.” Most of the time, there are no consequences. Nothing is done. The system is not working as it should.”

Jaquel Alexander Photo: ADOC

More recently, a 26-year old man committed suicide inside Donaldson Correctional Facility. On May 17, Jaquel Alexander was found unresponsive in a cell, according to Jefferson County’s Medical Examiner, who said Alexander’s death was likely caused by hanging. Court records show he was in prison on a probation violation and had a 2015 conviction for obstruction of justice.

Multiple sources have reported two other recent suicides in ADOC facilities in the past week, but ADOC has not yet confirmed those deaths.

Despite the DOJ findings that demanded ADOC implement reforms to curb violence and contraband, preventable deaths inside the prisons have continued unabated. So far in 2020, at least 9 people have died due to homicide, suicide or overdose in Alabama prisons.

In April, two men in ADOC prisons died due to violent circumstances. On April 19, Equal Justice Initiative reported Curtis Williams, 43, was taken off life support and died after he was stabbed inside Ventress Correctional Facility.

Levi Levorious Buckhalter Photo provided by Tonia Barnes

Also on April 19, Levi Levorious Buckhalter, 25, died after being removed from life support at a Mobile hospital. His mother, Tonia Barnes, said the warden of Fountain Correctional Facility called her a week prior and said her son suffered a head injury at the prison, but that she wasn’t sure how it happened.

“She said maybe he fell in the bathroom and hit his head on the sink,” Tonia said. “Then she asked me if he had seizures and I told her no, he has no history of seizures.”

Tonia was allowed to visit her son in the hospital before the prison decided to remove him from life support. She is waiting to learn his official cause of death from the autopsy results, and believes her son did not belong in prison. Levorious, as she called him, entered ADOC custody in December 2019 for a probation violation. His prior convictions included drug possession and credit card fraud.

“He was afraid he was going to die in there,” Tonia said. “He called me crying after getting jumped twice in one day by two other inmates. He was scared, but didn’t want to fight back because he was afraid he’d get in trouble.”

Like in so many other untimely deaths, ADOC responded by saying no foul play was suspected in Buckhalter’s death and the exact cause of death was pending a full autopsy. The losses add to an already unacceptable death toll in Alabama prisons, exposing ADOC’s continued inability to keep the people in their care safe from harm, with or without a pandemic.

“She didn’t even say his name.

Jason Reed and Misty Reed Tipton. Photo provided by Misty Reed Tipton

On the Monday morning after her brother’s death, Misty Tipton reached the warden of Bullock Correctional Facility by phone, Patrice Richie. Misty was hoping to learn more about what happened to her brother - where he died, how he died, who found him - but the warden would not share any details.

“I could hear her flipping through papers, but she wouldn’t answer any questions,” Misty said. “She was very rude and did not talk to me like a person who cared. She referred to him as ‘the inmate.’ She never even said his name.”

Warden Richie instructed Misty to call a funeral home and fill out a release form in order to claim Jason’s body. Misty did what she was told and called the prison later that day to inquire about obtaining her brother’s belongings. The warden’s secretary told her that as soon as the warden finished the paperwork, someone at the prison would call her about picking up Jason’s property. Misty still hasn’t heard back, despite leaving multiple messages for the warden and repeatedly calling ADOC headquarters.

“We understand the need to wait for autopsy results, but my brother was 35 and healthy,” she said. We don’t understand why no one at the prison will give us any information surrounding his death or even return our calls.”

Jason left behind two sons, ages 14 and 17. Misty said they have no idea what happened to their father and are struggling to understand that he is gone. Jason was her father’s only son, and she said the loss has hit him the hardest of anyone.

“My daddy is not one to show emotions, but I’ve seen him cry more in the last few weeks than I have my entire life,” Misty said while choking up. “I go and sit with him every day on the front porch and we don’t even talk, we just watch the cars drive by. That’s all we can do.”

Beth Shelburne is an investigative reporter for the Campaign for Smart Justice with the ACLU of Alabama. For investigative reporting on Alabama’s prison and pardons & paroles systems, follow her on Twitter at @bshelburne.