37 Years: A Long Road To Freedom

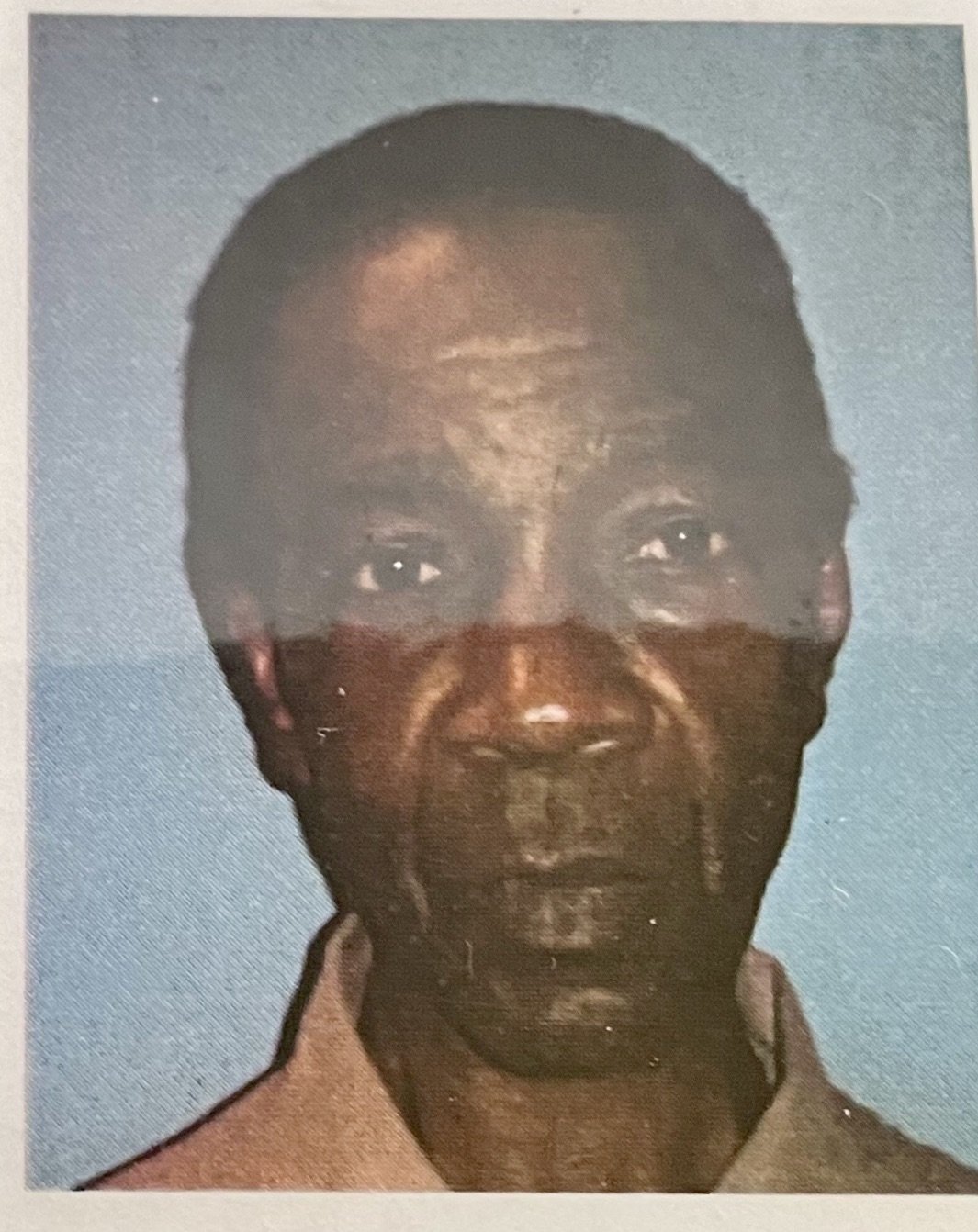

In 1985, Henry Towns was sentenced to life without parole under Alabama’s habitual felony offender act.

After 37 years of incarceration, he is released and finally home for Christmas.

This is how it happened.

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

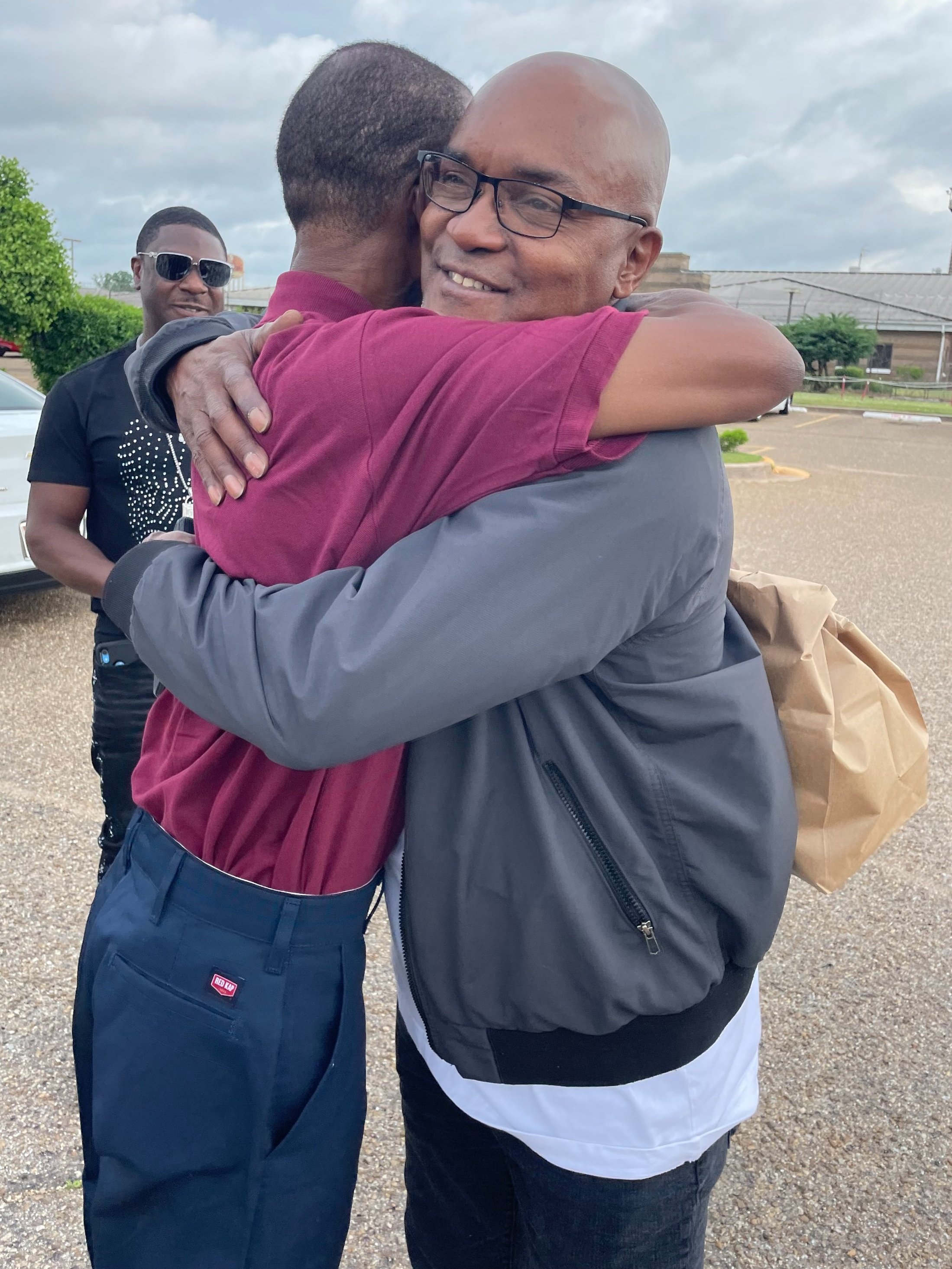

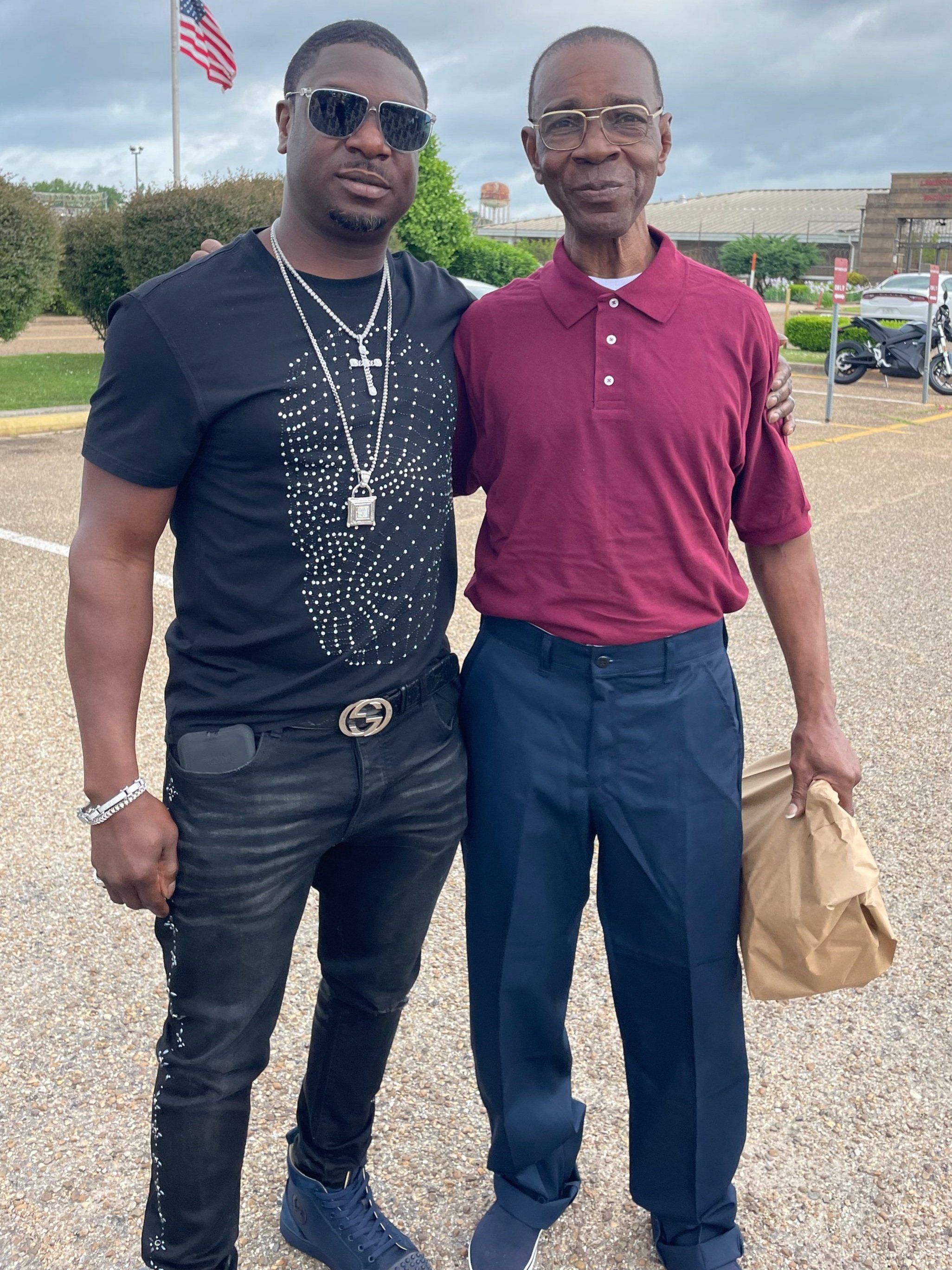

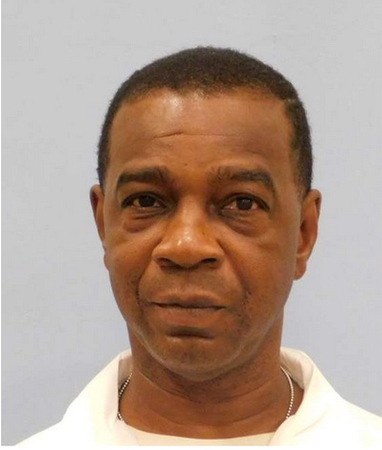

Dark clouds blanketed the sky over Limestone Correctional Facility the day Henry Towns was released, but to him, it was the most exceptionally beautiful day. He exited the front gate and inhaled his first breaths of fresh air in the prison’s parking lot, not exactly Shangri-La, but to Henry it would do just fine. It was May 3, 2022, and he’d been locked up in Alabama’s overcrowded and violent prison system since July 9, 1985: almost 37 straight years. The clouds over the prison weren’t thunderheads but stratocumulus, signs of a clearing sky.

A small cluster of people waited for Henry in the parking lot, and I was among them. Henry’s older sister, Lillian, her son Jimmy. Henry’s son, Tony Ford, drove over from Atlanta. Ronald McKeithen, who served time with Henry at Donaldson Correctional Facility and was released in 2020, was also there. We spotted Henry and his attorney, Greg Yaghmai, headed our way. Henry appeared thin, the blue slacks and burgundy shirt he changed into shortly before exiting the prison hanging off his 6-foot frame.

Lillian broke away from us, singing out, “Look at my brother!” and then with each step she took toward him, she said his name, “Henry. Henry. Henry.” When they finally reached each other, Henry and Lillian fell into a long embrace, Henry clutching a brown paper sack of his belongings in one hand and a white washcloth in the other. Lillian sobbed into his shoulder. “You comin’ home, Henry. You comin’ home. Oh Jesus! You comin’ home.”

The release of Henry Towns should not be unusual, but in Alabama’s criminal punishment system, where doors slam shut rather than open, where banishment is the rule and mercy is the exception, and where 93 percent of Black people like Henry were denied parole this year, it was highly unlikely that Henry would ever make it out of prison alive. Watching a 66-year old Black man walk out of prison after once being condemned to die is like watching a man walk on water. It just doesn’t happen, not in Alabama.

For a long time, Henry believed he would die in prison and that’s what the state wanted. The judge gave him two life without parole sentences, a “death-in-prison” fate under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act (HFOA) for drug-related robberies with no physical injury. Over the years he petitioned the courts for relief, filing so-called “Kirby” motions, named after a man who won relief in the courts from a life-without-parole sentence for drug trafficking, but Henry’s motions were denied each time. Then in 2014, Alabama legislators inexplicably passed a bill killing the “Kirby” rule, preventing Henry and others from seeking further help from the courts. Since then, all efforts to overturn or amend the HFOA have been scuttled, despite a Department of Justice lawsuit filed in 2020 demanding that Alabama address its prison overcrowding crisis.

Watching a 66-year old Black man walk out of prison after once being condemned to die is like watching a man walk on water. It just doesn’t happen, not in Alabama.

In many ways Henry is lucky. He had family support throughout his incarceration, including money to hire lawyers. The final hire was Mr. Yaghmai, his services paid for by Henry’s nephew Jimmy, a successful home builder in Tennessee. Yaghmai, himself a former prosecutor in the same office that sent Henry to prison for the rest of his natural life, filed a motion in Jefferson County court arguing that Henry’s sentence should be reduced because his prior robberies from 1979 did not involve a weapon. District Attorney Danny Carr did not oppose Henry’s motion and then, with the stroke of a pen, Judge James Hard finally resentenced Henry to life with the possibility of parole in December of 2019. It seemed all the stars aligned in Henry’s favor, but he would have to wait two more years for a parole hearing.

I attended that hearing in Montgomery on April 13, 2022 and the vote itself was the narrowest win possible, two to one. The board chair Leigh Gwathney, a career prosecutor, voted against Henry’s parole. Given Henry’s age and the relentless violence inside Alabama prisons, denying Henry a chance for release is akin to signing a death warrant. Thankfully, two out of three votes was enough to get him across the finish line. Henry and I later talked about how he barely made it out, and I asked him how he felt about the system so determined to keep him in prison. He shook his head and smiled.

“I’m just glad to be home,” he said. “It’s nothing personal. It’s not about the individual. The state is making so much money off keeping people in prison. It’s an industry.”

Henry and Lillian at his first meal after being released from prison.

Henry Towns is one of the people I have gotten to know in my reporting on Alabama’s habitual offender law and the people it threw away. The unremarkable robbery cases that landed him in prison were followed by a one-day, cursory trial, utterly devoid of humanity. The mandatory sentences of HFOA turned the system into a machine, chugging along to put people like Henry (mostly poor, Black men) on a conveyer belt into Alabama’s overcrowded prisons. Henry was sent there with no way out, no hope for a second chance. Not one thought was given to his family’s loss or the blow his absence might deal to his community. The system’s treatment of Henry, from his extreme sentence to his unlikely release, is commonplace and emblematic of the ironclad forces at work inside Alabama that still abide in an insistence that mass incarceration, at all costs, is the only way. Henry’s faith and fortitude prove them otherwise.

The mandatory sentences of HFOA turned the system into a machine, chugging along to put people like Henry (mostly poor, Black men) on a conveyer belt into Alabama’s overcrowded prisons. Henry was sent there with no way out, no hope for a second chance.

I visited with Henry in late October 2022 and hadn’t seen him since the day he got out. The caravan that picked him up from prison went to a celebratory brunch at a Cracker Barrel on the highway where he ate eggs, bacon and biscuits for his first meal. We all parted ways after the meal—Henry needed to go meet with his parole officer and was anxious to see his 91-year old mother, Lucy. He’s living with her now, helping to care for her and relieving some of the caretaking burden that his sister Lillian has carried for years.

I’d been to their house off Pratt Highway in northwest Birmingham once before, in 2019 when Henry was still trapped in a life-without-parole sentence. We had exchanged a few letters back then and he put me in touch with Lillian, who agreed to meet with me, along with Lucy, who was 88-years old at the time. The three of us sat at the kitchen table and talked about the family’s long struggle to reckon with Henry’s outsized sentence.

When I arrived at their house in October, Henry opened the door wearing a bright blue button-down shirt and a big smile. I noticed immediately that he’d gained some needed weight and appeared healthy and rested. He invited me in to sit at the same kitchen table where I’d visited with his mother and sister three years prior, when it seemed like Henry would never be able to come home. The three of them were just finishing up a pizza, and Henry was putting dishes in the sink and fussing over his mother, who smiled broadly the whole time I was there.

Henry Towns at home in October, 2022

Henry told me he was in the second phase of the “Day Reporting Center” program in downtown Birmingham, run by the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles. This was one of several conditions the parole board imposed on his release, along with 50 hours of community service. Henry had to report to the center every day, Monday through Friday for the first phase, which lasted almost five months. There, he attended classes and met with his parole officer, but said the program included too much down time—“just sitting around,” something Henry had done enough of after 37 years in prison. But he has a good relationship with his parole officer.

“She’s been there for me from day one,” he said. “She told me anything you need, let me know, and she’s been good on that.”

Henry didn’t attend his parole hearing because Alabama is one of the only states that doesn’t allow the person being considered for parole to address the board or attend their own hearing. His sister Lillian, nephew Jimmy, and attorney Greg Yaghmai testified on his behalf.

Yaghmai went first, giving the board some context for Henry’s crimes, telling them that after Henry served overseas in the Army, he came home with PTSD and self-medicated with drugs.

“It’s not a justification for his actions, it’s an explanation for why he got hooked on drugs,” Yaghmai said. “All of his crimes were a root of that.”

His nephew Jimmy told the board that he was 9-years old when Henry was arrested, but has maintained a close relationship with him over the years. “We have a very tight knit family, and even through all this time, he can pick up the phone and call ten people,” he said. The board members appeared to listen intently.

Lillian was the last to testify and told the board that Henry had been held accountable for his actions and expressed. She talked about the positive changes she saw in him over the years, and how he earned the respect of prison staff by being a leader inside the prison. “He’s 66-years old,” she finally said. “If you all would let him come home, so that his latter years can be with his family, we will take care of him, we will walk beside him, hug him and help him out.” She thanked the board and took her seat.

“He’s 66-years old,” she finally said. “If you all would let him come home, so that his latter years can be with his family, we will take care of him, we will walk beside him, hug him and help him out.” She thanked the board and took her seat.

The director of victim assistance from the Attorney General’s office, Sarah Greene, stood up to protest parole. Her perfunctory statement consisted of two sentences. She didn’t even say Henry’s name.

“We are protesting the release of this inmate today,” she said. “The court saw fit to sentence him to two life sentences. Our records show that there were two separate victims on these robberies where this inmate represented that he had a weapon on his person. And we would ask that you please deny and set him off for as long as you can. Thank you.”

The board then left the hearing room to go into executive session. They were gone for over 25 minutes while everyone in the room sat quietly, restlessly, an agonizing wait. The three board members finally came back to the hearing room, took their seats and recorded their votes. Gwathney announced the results.

“In the matter of parole for Henry Towns, Junior, in a vote of two to one, it is the decision of the board that Mr. Towns will be paroled,” Gwathney stated. She immediately then listed the terms of parole, that Henry would have to complete the Day Reporting Center program, with a warning of what would happen if he messed up.

“I can also tell you that if Mr. Towns chooses not to comply with the Day Reporting Center, he will go back to prison,” Gwathney said gravely. “We do not…look lightly upon people who fail out or stop going to the day reporting centers.”

I saw Lillian slowly nodding as Gwathney issued her warning. One wrong move and they’d send Henry back to prison in a heartbeat, but if anyone understood the mercilessness of Alabama’s criminal justice system, it was the Towns’ family. Lillian was focused on the mind blowing good news. She remembered thinking, “Did they really say parole? Did they really say it?” Her son grabbed her hand and she knew it was real.

Gwatheny ended her instructions by sharing that she’d voted against Henry’s parole. “It is Mr. Spurlock and Mr. Littleton who voted to grant parole,” she said. “It is Gwathney who voted to deny parole, but I wish him all the best and will be cheering him on just as well.” And with that mixed message, it was done.

The bailiff had instructed witnesses to not speak in the hearing room and a list of rules posted outside the hearing room included, “refrain from making any type of outburst.” Lillian, Jimmy, and Greg rose from their seats and filed out of the room, only able to finally share celebratory hugs after they exited. I snapped a photo of them outside the hearing room. Lillian’s smile could launch a rocket to the moon.

(L-R) Greg Yaghmai, Lillian Young, Jimmy Young

By the time I visited with Henry in October, he’d been out of prison almost six months and was working part time at the VA Hospital in Birmingham. He’d gotten his driver’s license just a few days after his release and fixed up an old truck that had been sitting in the driveway at Lillian’s house for over two years.

Over the summer, he undertook home improvement projects at his mother’s house—mowing the grass, pruning the yard, painting every surface that needed painting. He also spent a lot of time with his mother, Lucy, whose health has been declining in the last few years. She’s had thyroid problems, numerous surgeries and has trouble walking. Some days she gets confused or wakes up overnight in a state of bewilderment.

When Henry first saw his mother, he was shocked by her frailty, but in those first few weeks he walked with her, up and down their short hallway, her on a walker, his hand gently on her back. He’s also been cooking for her: “she’s very particular,” he said, and even though she can’t remember much of his life before prison, he’s trying to make new memories.

Everyone can see a difference in Lucy with Henry’s attention. “37 years in prison didn’t harden him,” Lillian said. “Him being here has really helped mother.” Lucy has gotten stronger and put on some weight. “She was sad all the time, but now I keep her laughing,” Henry said. “She’s happy and smiling. It’s like the light’s coming back in her.”

“She [his 91-year old mother Lucy] was sad all the time, but now I keep her laughing,” Henry said. “She’s happy and smiling. It’s like the light’s coming back in her.”

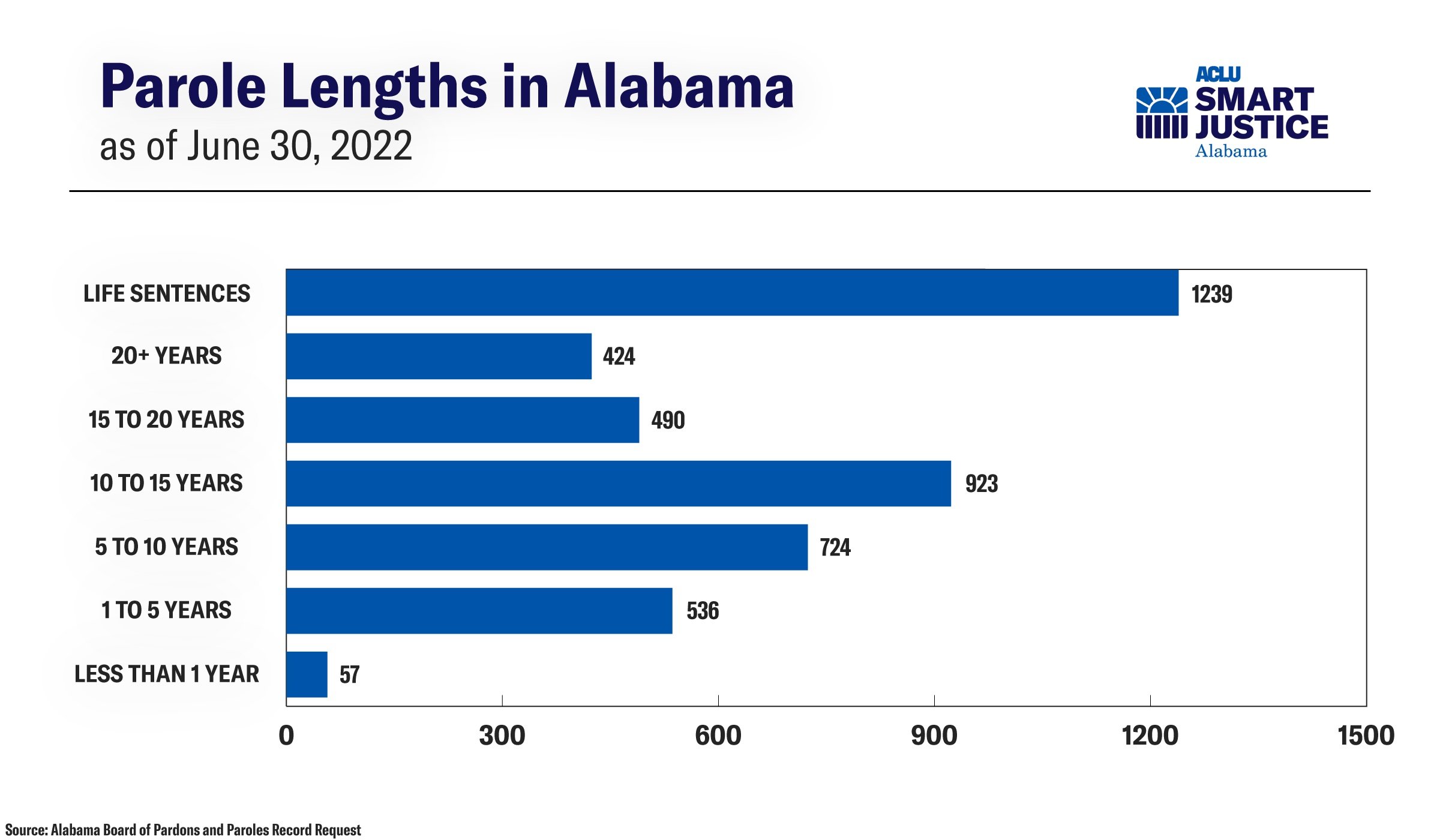

Part of the despair being felt inside Alabama prisons is a direct result of abysmal parole rates, particularly among Black people. Alabama tracks parole data according to fiscal year, and FY 2022 was a particularly brutal time for Black applicants. Henry was one of only 139 Black people granted parole during the entire year out of 2,054 eligible Black applicants who were considered. That’s a grant rate of just seven percent while white applicants were paroled at double that rate, or 14 percent.

Because Henry had a life sentence, he’s on parole for the rest of his life, unless he applies for and is granted a pardon. Once he finishes the Day Reporting Center program, he’ll still have to report regularly to his parole officer and pay a $40 monthly “supervision fee” that Alabama charges parolees. Henry didn’t have to pay the fee when he first got out, he had no income and couln’t work because he had to be at the Day Reporting Center each day, but once he got the job at the VA, the agency expected him to pay. On the day I visited him in October, he had taken $80 to their office because, Henry explained, they backtimed his payments to his start date with the VA.

“They said I was two months behind, so I took them $80 to get that straight,” Henry said.

After Henry was released, I was curious about how many people, like him, the state has put on parole for life, so I filed a records request with the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles asking for data. Of 4,393 parolees in June 2022, a total of 1,239 were serving parole for life, representing the largest segment of the parolee population, or 28 percent. If each of those lifetime parolees pays the required $40 supervision fee, that generates close to $50,000 a month for the state. As Henry referenced, the state isn’t just making money keeping people in prison, but also profiting from those that have been released, in perpetuity.

Henry is hoping the VA will hire him full time so he can upgrade his vehicle. His life outside of prison isn’t too glamorous or fast-paced, but he enjoys simple things, like breathing in fresh air outside in the morning. One of the first things he did when he got home was stand under the big magnolia tree in his mother’s front yard, placing his hand on the thick trunk.

“We don’t see trees (in prison),” Henry said. “I just went out in the front yard to touch it.” Being back in the wide, open world had been a long time coming.

Henry first wrote to me in 2017 when I was researching the habitual offender law and trying to make contact with people sentenced to die in prison for crimes that would not get that sentence today. Ronald McKeithen, who I was already in contact with, connected me with Henry when they were both serving life-without-parole at Donaldson prison.

In his letters, Henry described his prison experience in chapters marked by decades of time. The first decade he made wooden boats and jewelry boxes in the prison’s hobby craft room. The next ten years he worked in the prison kitchen as a baker. In the most recent decade, he felt like he needed more. Henry prayed for a change, and first entered and completed the prison’s drug program, then moved into the faith/honor dorm where he graduated from self-help classes like stress and anger management.

“I’ve been on a mission trying to better myself,” Henry wrote. “I’m not that young fool anymore. I’m a man who has earned his respect back by being a good example.”

Before I met with Lillian and Lucy in 2019, I had spoken with Lillian a few times on the phone. During those conversations, with the playful voices of her grandchildren in the background, she told me she visited Henry in prison every month, sometimes bringing Lucy with her.

Lucy Towns and Lillian Young at home in 2019.

The prison visits had grown especially difficult for Lucy, who was 86 back then, but was already relying on a walker to get around. Henry’s father, Henry senior, died in 2006 after running a successful service station in Birmingham’s Ensley community for over 35 years. For a long time Lucy dreamed about Henry getting out of prison and running the business, but over time her dreams grew simpler. She craved everyday interactions with her son, modest affairs that they’d missed over the years.

“She always tells me she is asking God to let her live long enough to see me walk out of here to just bring her a glass of water,” Henry wrote to me.

Henry grew up in Birmingham, but dropped out of high school in tenth grade, later earned his GED and eventually decided he wanted to join the military like his father, a World War II veteran. The Army sent Henry to Germany, where he began experimenting with drugs to cope with the 24-hour shifts he worked in a guard tower on base, using cocaine to stay awake and taking sleeping pills when he got off work.

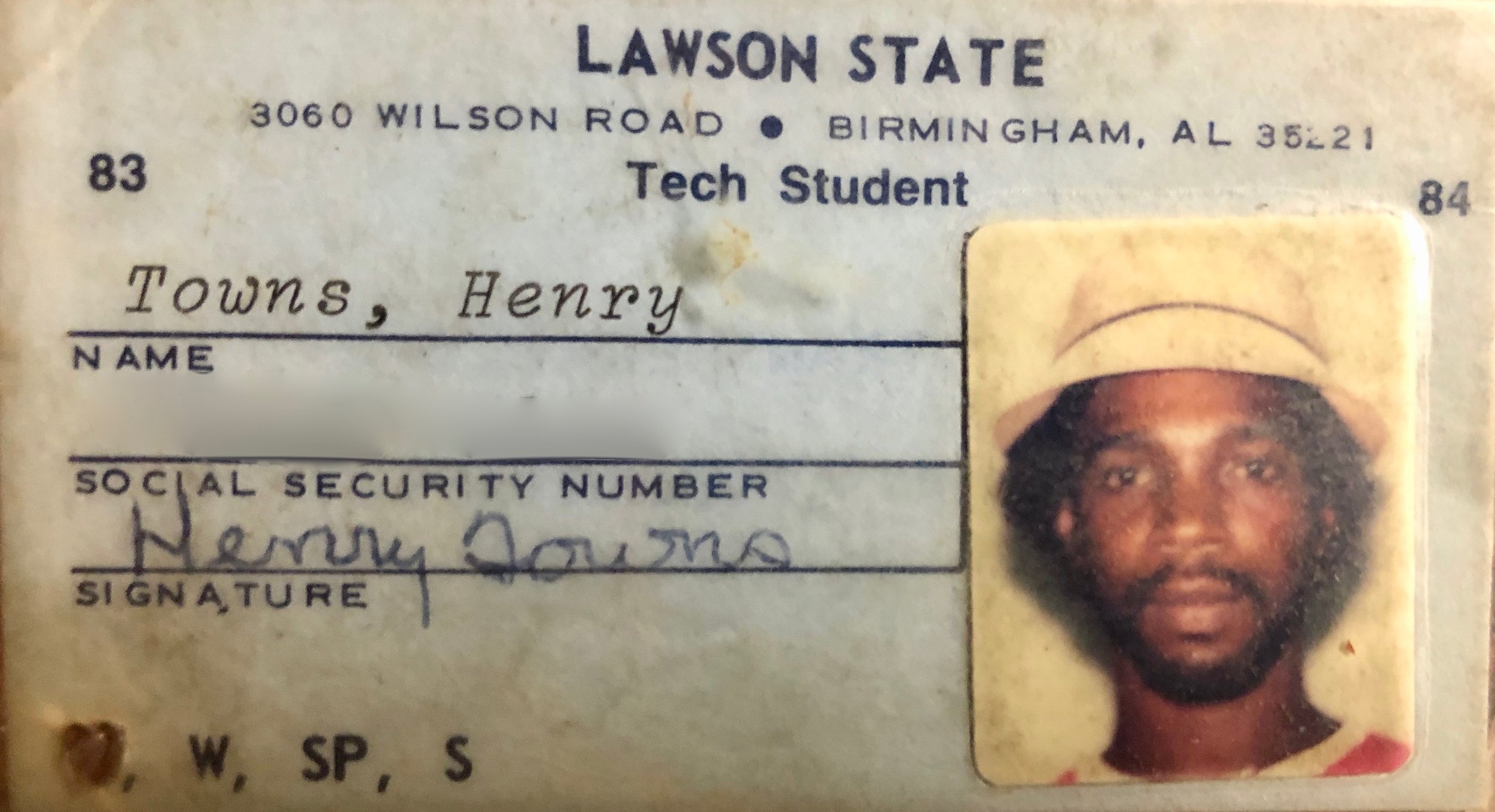

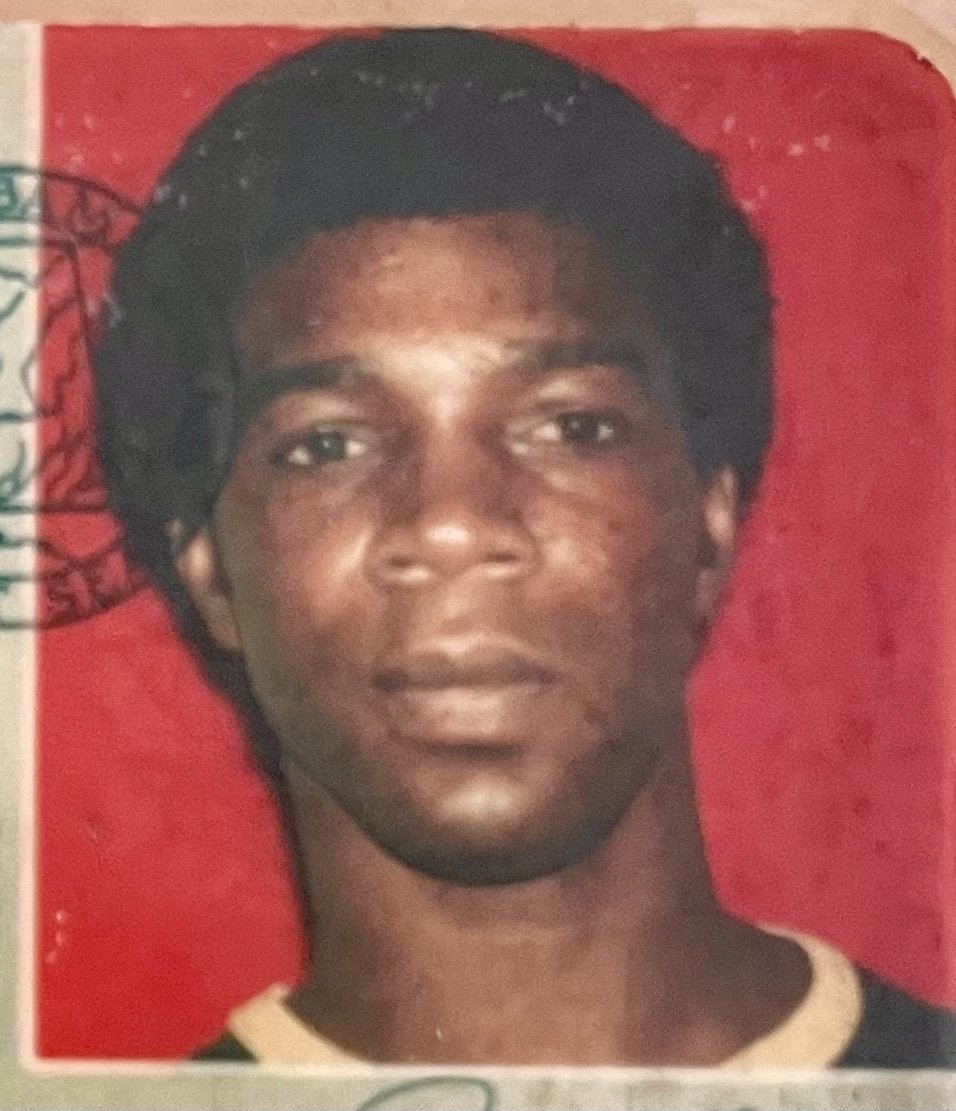

Henry Towns served as a infantryman in the U.S. Army

When he completed his tour with the Army in 1976, he came back to Birmingham and his family noticed he was withdrawn and didn’t want to talk about his time overseas. Henry was accepted to Lawson State Community College, but dropped out to work for the county bridge department. It was at this time in his early 20’s that Henry felt somewhat adrift, not knowing where life was taking him. Then he experienced heartbreak when a relationship with a woman ended badly and he fell into regular drug use. He thinks it was around 1978 when he began injecting a popular street drug of that era known as “T’s and Blues,” a sort of DIY heroin.

“We knew something wasn’t right with Henry when he came home from the Army,” Lillian told the parole board. “It really tore mother and daddy up.”

Henry tried to stop using drugs and decided to return to school. He borrowed money from his father to pay for tuition, but “blew it on dope” instead.

“I was too ashamed to go and ask him for more, so I made a stupid decision to take money from someone I figured wouldn’t do me body harm,” Henry wrote. He robbed two neighborhood stores and was arrested shortly after the second incident.

While he was in the county jail, police put him in several lineups and charged him with two additional robberies, crimes Henry maintains he did not commit. The Jefferson County DA’s office offered him a deal to plead guilty to all four and he’d get a 17-year sentence. He explained why he pleaded guilty to two robberies that he did not commit.

“I told my attorney that two of the cases were not mine,” he wrote. “He said that if we took this to trial, the DA would push for the max on all four. I accepted the deal and did the time.”

Henry served his time at Draper prison, and was paroled after four years. Back in Birmingham, he started dating a woman who also struggled with substance use, and Henry’s life slid off the rails again. He moved in with her and they went down a dark hole, buying drugs instead of paying for utilities. He said some nights they slept in the car to try to stay warm. He tried to find a job, “but at this time in 1985, nobody wanted to hire ex-cons,” he wrote.

Henry committed two more robberies of neighborhood stores, but in these he didn’t even have a weapon. He put his hand in a sock so the store clerks would think he had a gun. The total amount he stole from the two robberies wasn’t more than $121, according to Yaghmai.

Lillian and Lucy told me the family was extremely worried about Henry during this time, at wit’s end really, hearing from people in the community that he was slipping back into crime.

“He was not raised like that,” Lillian told me in 2019. “We are people that work for a living. And he was always helping his daddy. He learned to change tires while he probably was in elementary school. The drugs just messed him up.”

After the robberies, detectives came by Lucy’s house looking for Henry and left a card. Believing that the police could help him, that turning Henry in might save his life, Lucy called Lillian and asked her to call the detectives and let them know Henry was at her house.

“And I did,” Lillian recounted. “And the officers came and got Henry and slammed him up against the wall and he said ‘Mama, you called the police on me?’ and she said ‘Henry, I’m going to help you. You would have been killed out here in the streets, Henry.’” His family had no idea Henry faced a life-without-parole sentence if he was convicted.

The transcript from Henry’s one-day trial is shockingly thin. His court-appointed attorney called no witnesses and Henry did not take the stand. Lillian had to work and didn’t attend the trial, but drove to her mother’s house at the end of the day. She found Lucy in a state of total despair.

“She was just curled up on the floor like a baby, screaming and hollering,” Lillian said. Lucy told Lillian the judge had sentenced Henry to life without parole.

“You mean to tell me he got this for robbery?” she remembered asking her mother, the two of them thunderstruck with grief. Lucy clutched herself and sobbed on the floor, while Lillian sat with her mother in disbelief. The family knew Henry needed to pay for his crimes, but why did that mean for the rest of his life?

“You mean to tell me he got this for robbery?” she remembered asking her mother, the two of them thunderstruck with grief.

“Ever since then, we’ve been hiring lawyers,” Lillian told me in 2019. “They'll get the money and then say, there's nothing they can do to help him.”

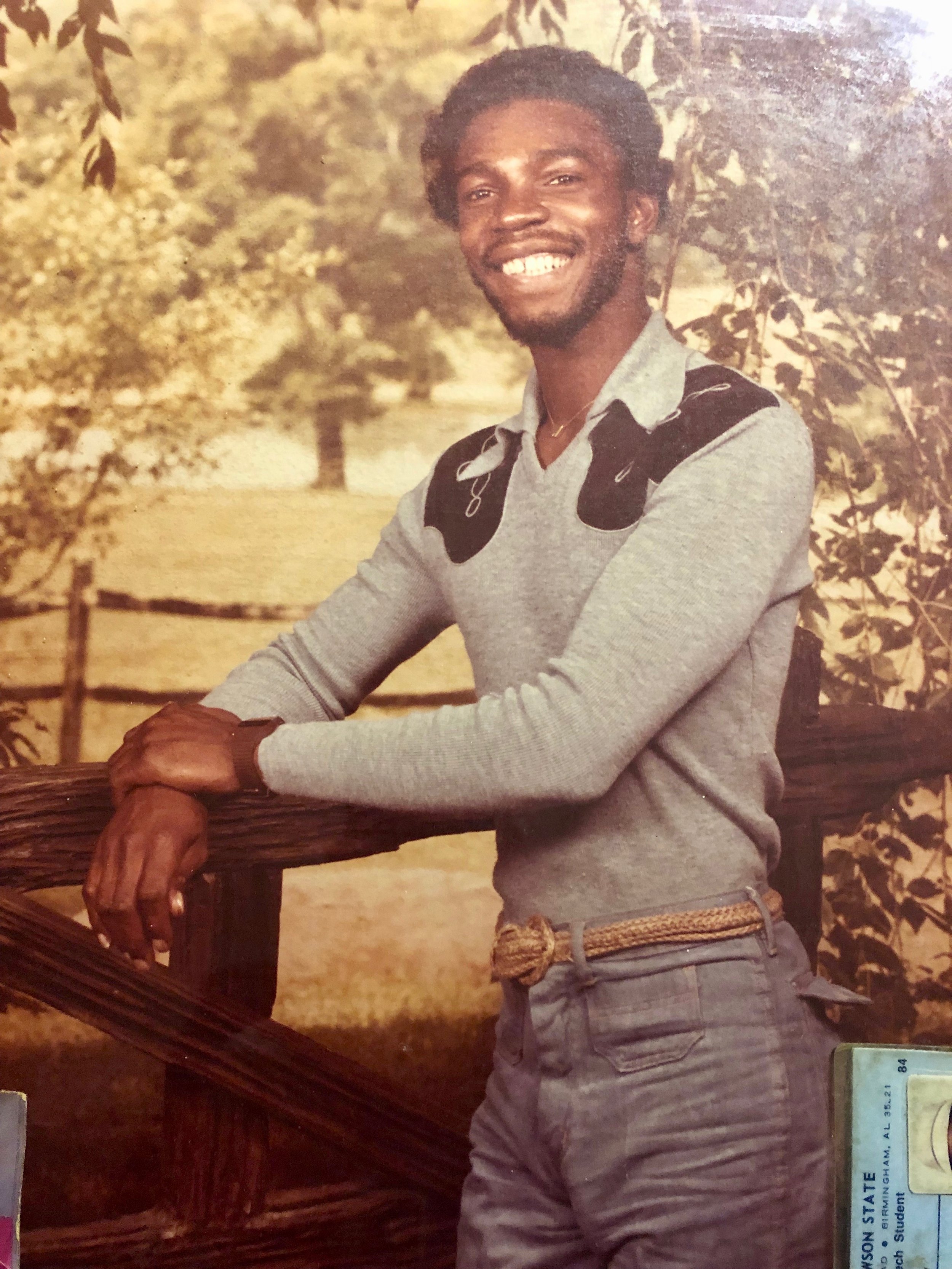

Henry and his son before 1985, when Henry was sentenced to life without parole.

When the family hired Yaghmai in 2019, hope was running thin. Yaghmai remembers Henry seemed resigned to his fate, afraid to place hope in yet another attorney who would not be able to unwind what the state had already done.

“My communication was, I’m not a miracle worker, but let’s see what we can do,” Yaghmai told me. “I think that gave him a little hope back.”

When Yaghmai worked in the Jefferson County district attorney’s office between 1997-2001, the same office that doomed Henry to a life in prison, Yaghmai said the office regularly pursued convictions under HFOA that often resulted in life sentences.

“If you had three prior felony convictions, no matter what they were, and you committed a class B felony, let’s say you stole a car that was worth $100, the minimum and the maximum was life,” he said. But over time, Yaghmai’s views on crime and punishment evolved. He left the DA’s office and did some criminal defense work. Henry was the first person he represented post-conviction fighting a life without parole sentence, and after successfully arguing for a sentence reduction, Henry became his first ever client to represent before the parole board.

“I think just growing up as a human being and being more mature makes you realize that not everything is so one-sided,” Yaghmai said.

Alabama’s habitual felony offender act was written by former Attorney General Charlie Graddick, who once bragged about his enthusiasm for capital punishment, telling a crowd of supporters that he’d “fry ‘em ‘til their eyeballs pop out and smoke pours out of their ears.” The legislature passed the HFOA into law in 1977 with the goal of reducing crime, but there’s never been data to show it worked. As early as 1985, the year Henry was sentenced to life without parole, criminologists began scrutinizing the cost of imposing lifetime sentences under the policy and found little public safety benefit.

Most of Henry’s incarceration was spent at William E. Donaldson Correctional Facility, the most violent prison in Alabama.

Supporters of the law say it impacts only the most violent repeat offenders, but the truth is many people like Henry were swept up in terminal sentences for petty, drug-related offenses, property crimes connected to poverty, and impulsive decisions of their youth, not deep criminality or dangerousness that would persist for decades. Efforts to amend the law with the goal of releasing older people who long ago ceased to threaten public safety have been quashed by Alabama’s Attorney General.

I’ve heard some prosecutors claim HFOA has practically become obsolete since Alabama enacted presumptive sentencing guidelines in 2013, but that’s not entirely true. While it may be true that less people are being sentenced under the policy, district attorneys can still choose to prosecute people with prior criminal records under HFOA in order to seek longer sentences or apply pressure on a defendant to accept a plea offer. This creates more disparity in sentences, with different people serving vastly different sentence lengths for similar crimes.

It also doesn’t change the reality that over 22 percent of the prison population, more than 5,000 people, are serving longer sentences under HFOA, in a system that has grown to contain 165% of the population it was designed to hold.

It also doesn’t change the reality that over 22 percent of the prison population, more than 5,000 people, are serving longer sentences under HFOA. In a system that has grown to contain 165% of the population it was designed to hold and where the Department of Justice as named overcrowding as the most dire condition to be remedied, the legislature’s unwillingness to amend this policy responsible for disparate and overblown sentences can only be viewed as deliberate indifference.

In FY 2022, 479 people sentenced under HFOA were serving life without parole, and 1,262 were serving life, according to the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) statistical reports. Many of these men and women are like Henry, serving decades in prison, long past the time any public safety argument can be made to justify their continued incarceration. And yet, time and again, when lawmakers bring a bill to address this policy’s overly punitive unfairness, it does not make it to the governor’s desk.

Even though Henry only had a handful of infractions on his prison record over his 37 years in state custody, his positive record didn’t seem to matter to the courts. Over the years, before his family hired Yaghmai, they paid different attorneys for his appeals, and all were denied. Henry filed two “Kirby” motions, the first was rejected in 2005, the judge writing in his notes, “As evidenced by the aggregate number of robberies, two committed while on parole, defendant is considered a violent offender and thus not Kirby eligible.”

Henry tried again in 2012, arguing in his neatly handwritten motion that he’d displayed no violent behavior in the 25 years he’d served in prison. He included dozens of certificates for programs he’d completed with names like “How to Worship” and “Long Distance Dads.” The court issued a two-sentence response that Henry received in the mail. “MOTION FOR SENTENCE MODIFICATION filed by HENRY TOWNS JR is hereby DENIED. DONE this 12th day of June, 2012,” the order stated. Henry wrote to me about his denied appeals. “I must admit I was disappointed, but I still have faith that one day I’m going home.”

Henry’s prior convictions were all for first degree robbery, which is a class A felony that will always be considered a violent offense. No one was ever physically injured in the incidents, but that is irrelevant in the strict legal definitions for his crimes. His family felt this was an unfair technicality, a murky interpretation of what Henry did a long time ago, and no reflection of who he became in prison. Lillian tried contacting state lawmakers over the years, but received no help or guidance on how Henry could ever receive a meaningful chance at freedom.

“He cannot get his case turned over for nothing,” Lillian told me in 2019. “All he wants is a chance for parole and he’s earned that. Henry is a changed man.” Three years later, Henry was free through a series of fortunate developments so unlikely in Alabama’s harsh climate that it felt like threading a needle with a spider web in a thunderstorm

As a free man on parole, Henry is busy, but still feels a bit like his life is in limbo. He’s living in his childhood bedroom, which his mother left untouched since 1985. In 2019 when I visited their home, Lillian showed me the room, coats still hanging in the closet where Henry left them when police slammed him up against the wall and took him to jail, his last moments as a free man.

In October when we visited, he was working four days a week at the VA hospital, but hoping the job would become full time. He goes to church every Sunday, sometimes on Wednesdays, and he told me he was thinking about joining his pastor in prison ministry work, to give back to the community he wanted to leave for much of his life.

“I think that’s what God wants me to do,” he said. “I know what those men want to hear. They want something to hold onto, something to look forward to. By me having two life-without-paroles and getting them off, that’s something that they want to know about. They need to hear it.”

He’s still processing all he endured in his 37 years under ADOC’s control. The last two years spent at St. Clair Correctional Facility were particularly alarming with drugs and violence part of the everyday. In a four month span, Henry saw six people die.

“We were taking care of ourselves in there,” he said. “The guards just stayed out of the way. Men were just dying, getting killed or overdosing. It was evil.”

“We were taking care of ourselves in there,” he said. “The guards just stayed out of the way. Men were just dying, getting killed or overdosing. It was evil.”

Talking to other people who have been through the process of coming home after prison has been a big help to Henry. Ronald McKeithen, who works as a re-entry coordinator for Alabama Appleseed, checks in on him. Henry enjoys attending weekly support groups with the Offender Alumni Association, a peer-support network of formerly incarcerated people who assist people coming out of prison. Like his time in the military, it seems like the only people who understand the battle and scars of prison are other people who made it out alive.

Yaghmai told me the experience of getting Henry out of prison remains a life-changing event for him, something he’s been proud to share with his college-aged daughter, an act that felt like pulling another human being to safety who was caught in a never-ending rip current, the tide refusing to turn.

Greg Yaghmai and Henry Towns

“Forget about my legal career, this was one of the most surreal, greatest experiences of my life to walk with him in the fresh air for the first time in 37 years,” Yaghmai said. “I’ll never forget walking out of those gates with him.”

Perhaps the person with the most gratitude for Henry’s freedom is Lucy, who finally reunited with her son after close to four decades of blaming herself for his imprisonment. She didn’t speak much when I visited her house in October, but her smile and joy in Henry’s presence was unmistakable. When Henry and I talked about his hopes, his plans, he kept coming back to the time he has with his mother. The family’s separation during his incarceration was an unbearable weight on everyone, but the love that bound them withstood the barriers, the hopelessness and all 37 years the state took from them.

“She is my top priority,” Henry said about his mother. “It was her prayers that got me out. My mama prayed and God answered. My life now is my mother and me.”